Part II: San Francisco, 1967

By Hayagriva das

Mad After Krishna

Printer

Friendly Page Printer

Friendly Page

Golden Gate

Park is redolent with March flowers. The morning fog disperses early,

and the days are cloudless and blue. Thousands continue to flock to San

Francisco from the midwest and east, and our Sunday kirtans

attract big crowds.

Sunday is

always a day for strolling in the park, and as soon as we start ringing

cymbals and chanting, people follow. Christian, Moslem, Jewish,

Buddhist and ISKCON banners, flying from long poles, proclaim our

ecumenism. We stake these in the field below Hippy Hill and set up the

kettledrum. Haridas, Mukunda, Shyamasundar, Subal, and Upendra sit in a

circle on the grass. We beat the rhythm slowly on the kettledrum, the

cymbals clash, and the kelp horn announces the beginning of kirtan.

After we

chant about an hour, Swamiji walks over from his apartment and enters

the center of the circle, clapping his hands and dancing, appearing

wonderfully bright in his saffron robes. He leads the chanting, playing

his own personal set of cymbals, a large pair with slightly flared rims

that resonate loudly. Although he is a half century older than everyone

around him, his presence is dynamically youthful. As the kirtan

soars, Swamiji is a child amongst children, dancing with hands upraised

to the blue sky, placing one foot before the other, dipping slightly,

encouraging everyone to dance.

Then

something remarkable happens.

The boys and

girls clasp hands and form a large circle around us. Another circle

encloses this circle, and suddenly Swamiji is in the center of two

circles of dancing, chanting youths. As the rhythm increases, the

circles begin to move more rapidly in opposite directions, everyone

holding on tightly, arms and hands joined, the circles jerking and

bouncing like great wheels rolling out of control, everyone short of

breath, laughing and trying to chant.

And Swamiji

urges us on.

“Hare

Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare.”

As the

circles rotate, around us pass kaleidoscopic images: pennants, bongos,

guitars, horns, cymbals, harmonium, sitars, tambourines, flutes, happy

faces, silver stars, dazzling sun, crescent moon, children, grass,

flowers, barking dogs, the ka-whoom of timpani, and Swamiji, dancing

gloriously in the middle.

“The way

those boys and girls were dancing in the park this afternoon,” Swamiji

tells us later, “that is the way Krishna was dancing the rasa-lila.

Because every gopi wanted to dance with Him, Krishna multiplied

Himself and danced like that in a circle beside each gopi, and

each and every gopi thought that Krishna was hers.“

After the

Sunday park kirtans, we return to the temple for the four

o’clock feast. Usually people stand outside waiting with paper plates;

inside, it is always packed. We receive little money from donations,

but Harsharani always manages to prepare enough kitri and halava.

The girls

often have difficulty serving everyone before people return for

seconds. I usually take my plate outside just to breathe fresh air.

Indians (from India) sometimes visit and stare in amazement at the

hippies accepting a culture that they themselves have rejected.

Do you know

who is the first

Eternal spaceman of this universe?

The first to send his wild vibrations

To all the cosmic super-stations?

For the song he always shouts

Sends the planets flipping out.

He sings to Virgo and the Pleiades,

For he can travel where he pleases…

But I’ll tell you before you think me loony,

That I’m talking about Narada Muni.

“Narada Muni

never stays any place longer than it takes to milk a cow,” Swamiji

tells us. “He carries a vina and is always chanting Hare

Krishna all over the universe. He is the first class, topmost devotee.”

Inspired by

this roving Vaishnava, Mukunda and I write a song that Swamiji

enjoys—“Narada Muni.”

O Narada

Muni, eternal spaceman,

Can travel much further than spaceships can,

Spreading sounds of love and joy vibrations

To all the cosmic incarnations,

Singing with bliss upon his vina,

The whole cosmos is his arena.

…Singing,“Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare,

Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.”

At this time,

a shipment of cymbals and mridangas—the Bengali clay

drums—arrives by air from India, ordered express by Swamiji, who

inspects every box carefully while unpacking.

“These drums

were designed by Lord Chaitanya Himself,” he tells us. “They are meant

especially for this sankirtan movement. And they give the

sweetest sound, a sound that can be produced by no other drum, with no

other material, because they are transcendental.”

He then

unpacks each mridanga, brushing off the excelsior, and inspects

the straps and heads minutely. When he plays one at kirtan, we

all instantly understand that a new and supramundane element has been

added. The

mridanga punctuates each Hare Krishna with an echo sounding like a

soul calling out for deliverance.

Afterwards,

Swamiji begins to teach Mukunda to play. “Tee-ka tee-ka tee.

Teo-ti-nak-tah, de tah de ta TAH.”

Because it is

a simple rhythm, one is tempted to speed up too soon.

“No,” Swamiji

says. “Slowly. Very slowly at first. You must play slowly and listen to

master it.”

No one really

masters mridanga. We all fumble in our own ways; only Swamiji

can play it properly.

On Tuesday

evenings, we go to the beach with Swamiji and hold unforgettable

Pacific Ocean sunset kirtans. Sitting on the sand, we watch the

tide roll in, or chant and wait for the sun to dip below the horizon.

“Pacific

means calm,” Swamiji says. “That is because it is so big and great.

When something is so great, it will naturally be calm because it has

nothing to fear.”

Haridas

builds a fire beside a sand dune, and we dance and chant around it.

Swamiji wears a scarf about his head, an old overcoat, and claps his

hands and chants, “Govinda jai jai, Gopala jai jai, Radharamana Hari,

Govinda jai jai.“

Holding hands

in a circle, we dance about the fire. Mukunda, Janaki, Shyamasundar,

Malati, and Haridas play cymbals and tambourines. I play trumpet.

Swamiji also dances, sometimes raising his arms in the air, sometimes

clapping. As the stars begin to shine bright over the Pacific, and the

foam and spindrift of waves recede in the dark, we sing “Narada Muni.”

“You must

write more such songs,” Swamiji tells us, “songs praising the acharyas,

great saintly persons. The

bhakta in love with God wants to sing to Him and His

representatives. And Hare Krishna, of all songs, is the supreme. It is

the call of a child for his father, a call of pure love. Oh, there are

many songs in the Vaishnava tradition, songs of Bhaktivinode Thakur,

and songs of Mirabai.“

After

chanting, we roast potatoes and smear them with melted butter. Swamiji

eats with us, sitting on a big log. And after potatoes, we roast

marshmallows, and red apples stuffed with raisins and brown sugar.

As Orion and

the Big Dipper shine brightly and the waves crash in the dark, we

gather about the fire for warmth, and one last Hare Krishna. After

this, we bow down on the sands, and Swamiji acclaims, All glories to

the assembled devotees! All glories to the assembled devotees! All

glories to the Pacific Ocean!”

And we all

laugh, Swamiji the loudest.

“But don’t

marshmallows have eggs in them?” Kirtanananda writes upon hearing.

Despite

initial difficulties, Kirtanananda opens a temple on Avenue du Parc in

Montreal. ISKCON now has three temples. Swamiji considers Montreal

auspicious because of the International Exposition there.

Before

Kirtanananda arrived, the temple was an abandoned bowling alley. He was

helped by Janardan, who has been claiming wide interest amongst

discontented French Catholics.

In triumph,

Kirtanananda mails us a feature article in Montreal’s Le Nouveau

Samedi. Headlines, in French: “THEY CLAIM THAT THE HINDU GOD

KRISHNA IS THE FATHER OF JESUS CHRIST AND THAT THE INHABITANTS OF THE

MOON ARE INVISIBLE.”

“Who says

they are invisible?” Swamiji asks. “In the Vedas, the

moon is considered a higher planet. There are demigods dwelling there

for thousands of years, and there they drink soma. You cannot

go there by artificial means, by rocket or space suit. No. You must

qualify to receive the proper body to take birth among the demigods.”

Kirtanananda

maintains the Vedic view before the smiling French Catholics,

dismissing Copernicus and Newton as mere material scientists bewildered

by a mechanical universe.

Kirtanananda

writes that he is managing to pay the rent by holding rock dances in

the bowling alley and taking in some boarders. Since he questioned the

propriety of marshmallows, I ask about holding such dances in the

temple.

“Well, there

would be no temple without money,” he writes. “Besides, the mantra

is an integral part of the dance, and the Vishnu altar is well lit with

many candles and incense. Altogether the atmosphere is really magical,

and I think it will even improve. The bands are most enthusiastic, and

though they have yet to perfect a good mantra rock style, I

think they will.”

Krishna, the

father of Christ. Invisible moon men. Mantra rock. The Montreal temple

is off to a good start.

“Isn’t

Krishna the eighth incarnation of Vishnu?” someone asks during a

question period.

“Krishna is

the original Personality of Godhead,” Swamiji says. “By Vishnu, we mean

Krishna. The four-armed Vishnu form is a special form manifested by

Krishna. Brahma creates, Vishnu maintains, and Shiva destroys. These

are all aspects of Krishna. But Krishna Himself has nothing to do but

enjoy. Therefore we see Him dancing with the gopis, in pure,

blissful, eternal pastimes.”

“And Rama?”

“He is also

the Supreme Lord, an expansion of Krishna who defeated the demon

Ravana. Hanuman was His servant, a monkey servant, who utilized his

wrath against Ravana. But when we chant Hare Krishna, Hare Rama, we do

not refer to this Rama but to Balarama, Krishna’s brother and His first

expansion. ‘Hare’ refers to Radharani.”

“And why is

Radha included?”

“She is

Krishna’s spiritual pleasure potency. It is not that Krishna is alone.

He is always with His beloved, the most elevated of the gopis.

When Krishna enjoys Himself, He expands as Radha-Krishna. Here in the

material world, what we call sex life is a perverted reflection of that

enjoyment potency. We should not consider Radha-Krishna in that light.

That is an offensive mistake.”

“What about

the demigods?” someone asks. “According to Bhagavad-gita,

by sacrificing to the demigods, man will receive all necessities.

“Yes. “

“Well, in

India, where these demigods are honored, people are poverty-stricken.

But here, no one believes in them, but there is plenty for all.“

“Just wait.”

A ripple of

laughter. Swamiji looks around, inviting more questions.

“Of course,

there is no need to worship the demigods separately, he adds. “Since

Krishna is the origin of the demigods, we worship Him, and the demigods

are automatically satisfied. Demigods are generally worshipped by the

less intelligent. ‘Those who worship the demigods go to the demigods,’

Krishna says. But that is a temporary situation. The devotees worship

Krishna and reach His supreme, eternal planet. India is in difficulty

now because we are turning from our Vedic culture and worshipping

Western technology. But you should also understand that your present

prosperity is due to pious activities in previous lives. There is a

point where the fruits of these activities run out.

Many Indians

visiting the Frederick Street temple tell us that they’ve never seen

such fiery, enthusiastic kirtans in India—nay, not anywhere

else in the world. A combination of magic elements is at work. First of

all, Swamiji’s presence. But remarkably enough, his presence is felt

even when he does not descend but stays in his upstairs apartment

writing his books. The unison kirtans intensify as new

instruments are added—flutes and tenor sax, trumpets and kettledrum,

cymbals and kelp horn, tambourines, mridangas, guitars and

bongos, sitars and castanets. Often we join hands and dance around the

walls of the temple, bounding on the floor and daring it to collapse. Kirtan

always begins with a rousing Hare Krishna. Then, after Swamiji’s

lecture, we chant “Gopala, Gopala, Devakinandana Gopala.” We first

heard this mantra sung by poet Ginsberg, and for a week Swamiji

tolerates it. Then he calls me in.

“That is not

a valid Vaishnava mantra,” he tells me. “You may change

Devaki’s name for Yasoda’s. Yasoda and not Devaki is accepted as

Krishna’s real mother because those matya-rasa pastimes were

carried on with her. But best not to chant that mantra at all

because it’s not authorized.“

Still intent

on some variety, we chant “Sri Ram Jai Ram Jai Jai Ram.“

“One Hare

Krishna is worth two thousand Jai Ram’s,” Swamiji remarks. “So why are

you wasting time?”

On Tuesday

and Thursday evenings, Mukunda gives music lessons, teaching different

melodies for Hare Krishna. And there’s also “Govinda jai jai, Gopala

jai jai, Radharamana Hari, Govinda jai jai,” which Swamiji sings so

beautifully at kirtan and upstairs alone, playing harmonium,

his voice full of devotion, alone with all the time in the world, time

no more a factor than space.

Even on the

nights that he does not descend, he listens to the kirtans in

his room. Afterwards, he smiles and asks, “It was a good kirtan,

yes? The hippies? They are appreciating? Yes, if they take up this Hare

Krishna, they will become transformed. And they will transform the

world. America is such a powerful country that all the world is

imitating. So just take up this chanting, make your country Krishna

conscious, and all the world will follow.”

Not all our

members are hippies or renegades from the hippy movement. There’s Jim,

the taxi driver, a very quiet, self-controlled young man who had gone

to Ohio State University.

“When driving

my cab, I was getting these headaches,” he tells Swamiji. “I’d get real

nervous driving. But then I started chanting Hare Krishna, and now the

traffic doesn’t bother me at all.”

He takes

initiation and is renamed Jayananda Das. He continues driving his taxi,

chants japa intensely, donates money to the temple, and

contributes every spare minute to Swamiji.

Another

non-hippy member is Mr. Morton, who is just completing his law degree.

He’s a little older than most devotees and seems to feel out of place,

but he continues attending, often wearing a hangdog expression because

he worries about his home life.

Poor Mr.

Morton. He can’t tear himself away from the chanting. Yet back home

there’s the wife and kids, and the wife disapproves of his consorting

with hippy cults. She also keeps reminding him that in the fall, they

have to return to Omaha to set up law practise.

Mr. Morton

buys big, red beads and strings them. He wears them around his neck and

chants sixteen rounds daily. At kirtan

, he stands in the middle of the temple, swaying back and forth, eyes

closed, beatific smile, enraptured.

“There is no

problem,” Swamiji tells him. “You can be a lawyer for Krishna. You can

be anything. But do it for Krishna. That’s bhakti-yoga.“

Mr. Morton

dons his hangdog expression again.

“But my

wife,” he says. “She’s already threatening to divorce me. And she

refuses to stop cooking meat.”

“Bring her to

kirtan,” Swamiji tells him.

He does. She

leaves after two minutes.

Mr. Morton

stays with the temple until his career and wife finally pull him away

to Omaha.

“He’ll always

remember these as the happiest days in his life,” I tell Haridas. “And

he’ll always wonder why.”

Then I stop,

hesitate, and think sadly that the same is possibly no less true for

myself. For all of us.

I got those

Samsara Blues,

Thinking, Good or bad? Win or lose?

All that smokin’ and takin’ meth,

Just turn the wheel of birth and death.

I’ll never attain liberation

By mere sense gratification.

LSD and marijuana

just won’t get me to nirvana.

And meditatin’ on the void,

Only gets me paranoid.

Remembering I’m not this body,

I tell her that I’m brahmachari.

So forget that Uncle Sam thing,

Just keep chanting, chanting, chanting.

…Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare.

In material entanglement, what calms me?

Why, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami.

Krishna, chase away those Samsara Blues!

A sincere

statement written by Haridas. For us, there is always the

lure of sex, milkshakes and chocolate bars, doughnuts, frivolous games,

Bach and Mozart, rock and roll, poetry and novels, travel, pot, peyote

and acid, and long, aimless talks over coffee or a glass of beer. Are

these forever to be denied?

Being

somewhat older—late twenties and early thirties—Haridas, myself and a

few others marvel over the apparent ease with which teenagers renounce

these common drives, inebriants, habits. “Maya is but Krishna’s

smile,” I try to remember.

“It should be

easier for you,” the younger members say. “You’ve been partying since

1958. We’ve hardly had a taste.”

Swamiji

supports another viewpoint.

“Best to be

trained up brahmachari from the beginning,” he says. “It’s

easier to renounce what you have never tasted. Once you are habituated

to intoxication, sex, gambling, meat eating, or whatever, it is very

difficult to give them up. Habits are hard to break. The urge for sense

enjoyment is the very cause of our conditioning. We forget that our

real enjoyment is in serving Krishna, and in being enjoyed by Him. In

ignorance, we become habituated to so many undesirable things. Now our

younger members are finding it easier to give up so much because

they’ve not had the chance to become addicted. But even addicted, you

reach a point where you see that there’s no happiness in sense

gratification. Frustrated by maya, you may turn toward Krishna.

But that is not the desirable road. The best way is not to forget

Krishna for a moment.”

“But Krishna

says that 'all roads lead to Me',” someone says.

“Where does

He say that?” Swamiji demands.

Swamiji’s

translation of the “roads” verse from Bhagavad-gita is

precise: “All of them—as they surrender unto Me—I reward accordingly.

Everyone follows My path in all respects, O son of Pritha.”

“That does

not mean that all roads lead to the same place,” he tells us. “Yes,

they are all Krishna’s roads, just as all the roads in America belong

to the government. But is that to say that all roads lead to San

Francisco? The devotees attain the person Krishna, and the

impersonalists attain the Brahman effulgence that emanates from

Krishna. The roads are all Krishna’s, but the goals are not the same.

In the material universe there are 8,400,000 species of life and roads

leading to each of them. They are all Krishna’s roads because He is the

Father of all living entities. But does this mean that we aspire to be

a cat or dog? Our aim should be to serve Krishna, that’s all. We do not

aspire to be demigods or whatever. Lord Chaitanya had but one request:

causeless devotional service life after life, regardless of the type of

body. Hanuman served Lord Rama very well in a monkey body.”

Yet many of

us stumble on the road of Krishna consciousness and fall back into our

old ways. How can we channel everything to the person Krishna? There’s

music, fast cars, intoxicants, and golden California lasses calling,

“Fun, fun, fun!”

Srila

Prabhupada tells the story of a young prince who became attracted by a

beautiful girl who happened to be a devotee. Just by seeing this girl

once, the prince fell in love with her and made arrangements with her

father for marriage. But since the girl was devoted to Krishna, she

refused him. “Oh, your beauty has captivated me,” the prince said. “If

I cannot have it, I will kill myself” Understanding the situation, the

girl said, “Come back in two weeks, and my beauty will be yours.” The

prince went away, but when he returned after two weeks, he hardly

recognized the young girl. Because she had taken a very strong

purgative that had flushed her body of all liquids, she was shrivelled

and emaciated like an old hag. “You want my beauty?” she asked the

horrified prince. “You will find it there in the corner.” And she

pointed to a pot full of stool and vomit. “There is the beauty you

desired,” she said. “Take it and be happy.”

Ramanuja-das-brahmachari

automatically turns to admire a pretty girl.

“That’s just

a combination of blood, pus, and stool,” I remind him. “Of bile, urine,

flesh, phlegm, bone, and guts.”

“Yes,” he

says, “but it’s all in the right place.”

“Miss Maya is

so strong,” Swamiji tells us, “that when she sees you trying to become

Krishna conscious, she’ll knock you down.” He shakes his head and

smiles, as if facing an unconquerable foe. “She is so strong, and we

are so weak. Like fire and butter. We should never think that we are

stronger than Maya. We have only one recourse Hare Krishna. When

Mayadevi attacks, we must cry, ‘Krishna! Krishna! Please save me!’

Since only Krishna is stronger than maya, only Krishna can

protect us. When the pure devotee conquers Krishna through love, then

Mayadevi stands before the devotee and says, ‘How may I serve you?’

Only then does maya cease to be a foe. Only then is maya seen

as Krishna’s smile.“

It seems that

the girls have less trouble surrendering. They just throw themselves

in, crying, “Krishna! Krishna!”

“Women are

soft-hearted,” Swamiji says, “but unfortunately they are fickle, too.

They are quick to accept and reject. They come to Krishna consciousness

quickly, out of sentiment, and then some boy comes along, and they

reject everything. Men are not so quick to accept, but once they have

accepted, they are more reluctant to reject. So the male is considered

a higher birth because a man is more likely to understand Krishna

consciousness and therefore remain steady. In Vedic culture, the woman

is considered weak. Soft-hearted. She should be protected, not given

freedom to roam about, like in this country. Therefore we are marrying

our girls to nice Krishna conscious boys.”

Someone

suggests that perhaps it is easier for girls to surrender to a male God.

“That is a

material consideration,” Swamiji says, “because the soul is neither

male nor female. All-attractive means that Krishna attracts all. But

Krishna is always the male, the enjoyer, and in respect to Him, the jiva-atma,

or individual soul, is always female, the enjoyed. When the female

attempts to imitate the male, the result is topsy-turvy, is it not?

“So, devoid

of Krishna consciousness, the conditioned soul is enjoy-less. Lots of

zeros add up to zero. We must put the one before the zeros. Krishna is

the missing one giving joy to all the infinite zeros. ‘Aham

bija-pradah pita.’ I am the seed-giving father.”

A society

columnist from The San Francisco Chronicle interviews

Malati and her “gopis.” “These

gopis,” the columnist writes, “are cowherd girls. They wear saris

and will be glad to perform kirtan anywhere.”

Apparently,

the lady’s column is widely read. We are bombarded by phone calls from

socialites who want Malati and her

gopis to perform in their homes. When we are invited by one of the

richest families in San Francisco, the Thompsons, Malati accepts.

I suggest

that since it appears a ladies’ affair, she can take the gopis

herself, but Malati informs me that the girls are afraid to go alone.

Somehow twelve of us manage to pile into Shyamasundar’s old Chevy. En

route, we’re pulled over and ticketed for an overloaded vehicle.

We’re met at

the door by bewildered servants; the columnist had written nothing

about the male hippies accompanying the female gopis. There’s

much scurrying about and whispering amongst the Thompsons and their

servants before we’re allowed in.

From the

beginning, the evening is disastrous for everyone. It seems that we

were invited to a party of wealthy, drunken, middle-aged socialites

mainly to entertain while the rock and roll band refurbished their

drinks.

Not knowing

what to do, I give a little talk about Swamiji’ s mission in America,

his founding of ISKCON and the New York and Frederick Street temples,

and the meaning and purpose of the mantra. We then start

chanting, but after a minute

we’re interrupted by a drunk and belligerent old man.

The Thompsons

are too drunk to be embarrassed. Mrs. Thompson gives Malati a hundred

dollar donation, telling her that everyone appreciates “the good work

you’re doing, reforming the drug addicts down there.” We then fold up

the harmonium, gather our cymbals and leave quickly.

“You should

not chant or explain the mantra before such people,” Swamiji

tells us afterwards. “Actually, Krishna tells Arjuna that Bhagavad-gita

should be explained only to the pious. Of course, now in Kali-yuga

people are mostly in passion and ignorance, so if we preach just to the

pious, we’ll have no audience. It is Lord Chaitanya’s desire that this

chanting be preached in every village in the world, and His desire is

the purpose of ISKCON. So we are preaching to the hippies. But we need

not attend the parties of drunkards.”

Swamiji calls

me into his room. I bow and sit facing him, sensing something special.

“I am

thinking it will be nice if you write a play about Lord Chaitanya,”

he tells me. “I will give you the whole plot complete. Then all you

will have to do is execute it.”

For two days,

I sit in Swamiji’s room listening to his account of the life of Lord

Chaitanya. At this time, Swamiji is also lecturing on the Chaitanya-charitamrita.

There is also a translation of Chaitanya-charitamrita

going about, translated by Nagendra Kumar Roy. Swamiji reads a bit of

this translation and quickly finds a discrepancy. It is over one word,

“rheumatism,” which has been translated incorrectly from the Bengali.

Swamiji immediately brands Mr. Kumar Roy a sentimentalist. The

translation is inaccurate. Throw it out.

“I will give

you all you need to know,” he tells me.

I tape record

the outline and interrupt only when the action isn’t clear.

On the second

day, Swamiji tells of the passing of Haridas Thakur, one of Lord

Chaitanya’s principal disciples. Recounting the details, Swamiji

becomes strangely indrawn, as if it were all happening before him.

“When

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu visited Haridas on the last day of Haridas’s

life,” Swamiji says, “the Lord asked, ‘Haridas, what do you desire?’

They both could understand. Haridas said, ‘It is my last day. If You

would kindly stand before me…’” Swamiji suddenly falls silent a moment

and looks down at his hands. “So Chaitanya Mahaprabhu stood before

him,” he continues, speaking softly, his eyes filling with tears. “And

Haridas left his body.”

Then Swamiji

sits there crying silently within. It is a silence I can hear above the

street noises and hum of the tape recorder. I stare at the floor, then

look up, embarrassed, feeling I shouldn’t be in the room. As I begin to

ask a question, Swamiji again speaks.

“After his

departure,” he says, “the body was taken by the Lord to the seashore,

and the devotees dug his grave, which is still there, Haridas Thakur’s samadhi.

And Chaitanya Mahaprabhu took up the dead body and began to dance with

the body at kirtan. Thus Haridas’s funeral ceremony was

conducted by the Lord Himself.“

And Swamiji

continues outlining the play as though nothing had happened, his

sudden, silent weeping passing with the wind.

Although I

write on the Lord Chaitanya play through the spring days, my primary

service is helping Swamiji with

Bhagavad-gita. He continues translating, hurrying to complete

the manuscript but still annotating each verse thoroughly in his

purports. Daily, I consult him to make certain that the translation of

each verse precisely coincides with the meaning he wants to relate.

“Edit for force and clarity,” he tells me. “By Krishna’s grace, you are

a qualified English professor. You know how grammatical mistakes will

discredit us with scholars. I want them to appreciate this Bhagavad-gita

as the definitive edition. All the others try to take credit away from

Krishna.”

I am swamped

with editing. Since much of the text is equivocal due to grammar, I

find myself consulting Swamiji on nearly every verse. It seems that in

Sanskrit, Hindi, and Bengali, phrase is tacked onto phrase until the

original subject is lost.

No one has

yet asked Swamiji the language in which he thinks. Bengali, I presume,

but for all I know it may be Hindi or Sanskrit. He often says that

Sanskrit is the language of the demigods, the original language, and

that all other languages descend from it. Indeed, it was the very

language used by Krishna when He spoke Bhagavad-gita

millions of years ago to the sun god Vivasvan, and then five thousand

years ago to Arjuna at Kurukshetra. All seven hundred verses sung in

Sanskrit.

Swamiji

sweeps away archeological and philological pronouncements with a

disdainful sweep of his hand.

“What do they

know? Great civilizations were existing on this earth hundreds of

thousands of years ago. They are thinking that everything begins with

them, with cavemen or monkeys. But in ages past, Maharaj Bharat ruled

the entire world, and there were great civilizations everywhere. Who

can deny that Sanskrit is the mother of languages? So-called scholars

are simply concocting nonsense, proposing theories. Their business is:

‘You propose a theory, and I propose a greater theory.’ But Bhagavad-gita

is not theory. It is fact. Therefore I am presenting it as it is. Not

as it seems to me, but as it is spoken. Radhakrishnan says that we are

not to worship the person Krishna, and Gandhi says that Kurukshetra is

a symbol for this or that, but these are all opinions. Mental

speculations. To expose them, we must quickly publish Bhagavad-gita

As It Is. Someone has told me that the purports are very

lengthy, but that is the Vaishnava tradition—constantly expanding. The

purports are intended to bring the meaning back to Krishna, to rectify

the mischief done by these rascal commentators. Factually, this is the

only authorized translation. So I am eager to see our Bhagavad-gita

published complete.”

In New York,

Brahmananda continues negotiations with publishers. Swamiji consults

more private printers in San Francisco. Since it is turning into such a

lengthy book, it will be expensive. Swamiji also wants to include the

Sanskrit Devanagari, which will cost extra. Prices are way out of our

reach. We are still trying to scrape together rent for the temple and

Swamiji’s apartment. In New York, it’s the same. And Kirtanananda might

get kicked out of the bowling alley any day. None of us really wants to

count the assets of the International Society for Krishna

Consciousness. Really, we have only one asset—His Divine Grace himself.

March 21.

Swamiji has been discussing Srimad-Bhagavatam. His

lecture ends, and he asks for questions. No one speaks, and he asks

again and waits.

“There must

be questions,” he says.

Govinda-dasi

timidly raises her hand, and Swamiji acknowledges her.

“Can you

explain about Lord Chaitanya asking the whereabouts of Krishna in the

forest? Or would that not be a good thing to discuss?”

“Yes, Yes,”

Swamiji says happily. “Very nice. Your question is very nice. I’m very

glad. Lord Chaitanya was the greatest devotee of Krishna, and we should

think about His life. He never said, ‘I have seen Krishna,’ but He was

mad after Krishna.” Swamiji stresses the word “mad,” prolonging the

single syllable until we have visions of Lord Chaitanya dancing and

trembling in ecstasy. “He was always thinkng, ‘When shall I see

Krishna? Where is Krishna? Where is Krishna?’ He was so mad after

Krishna. And that is the main point of Chaitanya philosophy. This is

called worship in separation. The devotee thinks, ‘Krishna, You are so

wonderful, and I am such a fool and rascal that I cannot see You. I

have no qualification to see You.’ In this way, we should feel the

separation of Krishna, and these feelings will enrich us in Krishna

consciousness. It’s not, ‘Krishna, I’ve seen You. Finished.’ No.

Perpetually think of yourself as unfit to see Krishna. That will enrich

you.”

Swamiji nods

thoughtfully and looks at each of us. We do not speak, nor do our eyes

leave him.

“Yes,” he

continues, “when Krishna left Vrindaban for His father’s place,

Radharani was feeling in that way, always mad after Krishna. So

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu displayed these feelings of Radharani, and we

should understand that this is the best way for worshipping Krishna and

becoming Krishna conscious.”

He stops

again, waits, thinking, then goes on.

“You know

that Chaitanya Mahaprabhu threw Himself in the sea, crying, ‘Krishna,

are You here? Krishna, are You there?’ And Lord Chaitanya’s direct

disciples, the Goswamis, Rupa and Sanatan Goswami, also worshipped

Krishna in that feeling of separation. There is one nice verse about

them.”

He begins to

chant ecstatically, his voice rich and full.

he

radhe vraja-devike cha lalite he nanda-suno kutah

sri-govardhana-kalpa-padapa-tale kalindi-vanye kutah

ghosantav iti sarvato vraja-pure khedair maha-vihvalau

vande rupa-sanatanau raghu-yugau sri-jiva-gopalakau.

“I offer my

respectful obeisances to the six Goswamis—Srila Rupa Goswami, Sri

Sanatana Goswami, Sri Raghunatha-bhatta Goswami, Sri Raghunatha-dasa

Goswami, Sri Jiva Goswarm and Sri Gopala-bhatta Goswami—who were

chanting very loudly everywhere in Vrindaban, shouting, ‘O Queen of

Vrindaban, Radharani! O Lalita! O son of Nanda Maharaj! Where are You

now? Are You on Govardhan hill, or under the trees on the Yamuna’s

banks? Where are You?’ These were their moods in Krishna consciousness.“

He pauses,

closes his eyes, then speaks again.

“Later on,

when the Goswamis were very mature in devotional service, they were

daily going about Vrindaban, just like madmen, crying, ‘Krishna, where

You are?'...

After this,

Swamiji says no more but sits cross-legged on the dais, hands folded,

eyes closed in sudden, unexpected, rapt meditation. It’s as though he’s

been struck by a bolt from the blue. As we sit watching him, we all

suddenly feel an electric, vibrant stillness settling over the temple.

This is something very unusual, we all sense, yet dare not speak, dare

not look at one another, dare not take our eyes from him. Perceivable

spiritual phenomenon! We can actually see him withdraw deep within

himself and leave the body, the temple, the city, the world far behind,

so deep is his communion. We bathe in this intense silence for only

three or four minutes, but, as in earthquakes, those minutes seem

eternal for us all. But unlike earthquakes, there is no tumult. Just an

awesome stillness prolonging those minutes more than tumult ever could.

We see his

consciousness return to his body. He clears his throat, slowly opens

his eyes, and reaches for the cymbals beside him.

“Let us have kirtan,”

he says quietly, and begins chanting “Govinda Jai Jai".

Afterwards,

Subal runs up to me, his blue eyes popping.

“Did you see

that? Did you see it?”

We all begin

speculating on what had happened. We call it “the samadhi

lecture.” It’s the subject of whispered conversation for days.

It looks as

though Mr. Payne, the real estate agent, absconded with the $5,000

temple deposit. Swamiji talks to Brahmananda long distance.

“Get Mr.

Goldsmith, our lawyer,” he tells him. “We must retrieve the money.”

Brahmananda

admits that it is his fault; he gave Mr. Payne the money without a

proper contract. Suddenly he must pay the balance or lose the $5,000.

“These young

boys have been tricked,” Swamiji says. Then he shakes his head. “Money

is such a thing! Once money is out of your hand...” He waves his hand

in the air, as if flicking off water. Then he laughs. “It’s gone.”

But this,

among other matters, presses Swamiji to return to New York.

Unfortunately, Mukunda has only one speaking engagement for him at

Berkeley, April 6. Beyond that, nothing. Brahmananda writes of scores

of engagements lined up in New York, Philadelphia, and Washington. And

there’s the new Montreal temple to visit.

“Perhaps

Brahmananda can arrange for me to speak to your President Johnson,”

Swamiji laughs. “That is very difficult, no? And yet people are talking

of speaking to God. What does a man think he is that God should come

before him? And rascals are saying, ‘I am God.‘"

Brahmananda

mails a tape recording of all the New York devotees telling Swamiji how

much they miss him. It is a desperate plea for him to return. Mukunda

and I flinch as Swamiii listens sympathetically.

“It’s

Brahmananda’s plot to get him back,” I tell Mukunda afterwards.

The same

evening, Swamiji informs us that he is flying to New York April 9. Make

reservations immediately.

A bread truck

passes down Frederick Street and turns up Stanyan. Swamiji sees it from

his apartment window. “Simply Delicious!” is painted in large letters

on the bread truck.

Swamiji

laughs. “Simply dangerous,” he says. “This material world is simply

dangerous. Death is always standing beside us, waiting. For the

nondevotee, Krishna comes as death. But for the devotee, death comes as

Krishna.”

April 6: The

Pauley Ballroom on the University of California’s Berkeley campus,

center of student Vietnam war resistance. About five hundred students

come to hear Swamiji discuss the nature of the soul and give his peace

formula.

The format is

the same as always—chanting, lecture, question period, more chanting. A

very loquacious, effeminate Negro dominates the question period.

“Swamiji,

what’s my name?” he asks.

Swamiji

cannot see him; he’s just a voice in the crowd.

“Your name is

Krishna-das, he says.

“What does

that mean?”

“Servant of

Krishna.”

“Why servant?”

“Because in

relation to Krishna, it’s our constitutional duty to serve. The fingers

serve the hand; the parts serve the whole. As eternal parts of Krishna,

it’s our duty to serve. But how? That you must find out.”

“But I’m not

serving Krishna.”

“Then you are

serving maya. But serve you must.”

“I serve

myself.”

“Yes,”

Swamiji says patiently. “You serve your senses. Your tongue says, ‘Take

this nice food,’ and you eat. The eyes say, ‘See this nice girl,’ and

you look. So how are you not servant?”

No reply.

“You must

serve. Either maya or Krishna. If you master your senses, you become

goswami. And with purified senses, you can serve Krishna. That is your

perfection.”

“But why

serve at all? Why all this emphasis on service in the first place?”

“Because it

is our nature to want to serve someone we love. We want to do something

for our beloved. Is that not natural?”

“Yes. I guess

so.”

“Why guess?

You must know. If love for a person is there, some form of service

follows. It must! That is our happiness, that service, our eternal

happiness. Therefore we must cultivate love for Krishna.“

The students

join in the chanting but afterwards leave the auditorium shaking their

heads. They are skeptical. For them, Vietnam is life’s main problem,

the only thorn in the side of happiness. So how is Hare Krishna really

going to end the Vietnam war?

“Wars are

always going on. In Kali-yuga, men fight over nothing,” Swamiji says.

Press

coverage of the meeting is most offensive. A Berkeley Barb

reporter writes that “the female devotees in their exotic costumes

reminded me of harem dancers from a forgotten Hollywood epic.” The

reporter also admits spending most of his time watching “a decidedly

uninhibited young lady successfully levitate her miniskirt by means of

vigorously erotic calisthenics.” And so on.

Worst of all,

Swamiji’s peace formula is criticized: “Easy things are nice, but easy

things don’t work.”

We don’t dare

show the article to Swamiji. Enraged, I phone The Barb.

“We’re really

offended,” I tell the editor. “Our brahmacharinis certainly

don’t look like harem dancers.”

“The writer

has the right to his subjective opinion,” the editor says.

I agree to

this, but catch them on a philosophical error. When the Negro asked who

he was, Swamiji is reported as saying, “You are God.“

“This is

impossible,” I say. “He said, ‘You are a servant of God.’”

Yielding to

this point, the editor prints a retraction, adding: “In this way the

Swami’s religion differs from that of Timothy Leary. Leary likes to

tell humans, ‘You are God.’”

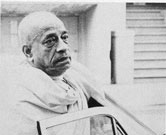

April 9:

Swamiji leaves for the airport. Before entering the car, he stops, cane

in hand, and gives a long look at the little storefront temple. It is a

look that says a great deal. Gurudas snaps a photo at that very instant. April 9:

Swamiji leaves for the airport. Before entering the car, he stops, cane

in hand, and gives a long look at the little storefront temple. It is a

look that says a great deal. Gurudas snaps a photo at that very instant.

“That’s a

farewell look,” I think to myself.

At the

airport, the girls cry. Swamiji quiets them by assuring us that he will

return for Lord Jagannatha’s Rathayatra festival on July 9.

“You must

arrange a procession down the main street,” he tells us. “Do it nicely.

We must attract many people. They have such a great procession yearly

in Jagannatha Puri. At this time, the Deity may leave the temple.”

We watch him

disappear down the passenger corridor to the plane.

Back at the

temple, I clean his upstairs apartment and keep his bedroom as an altar

room. Although wanting to return to New York, I must follow his

instructions to maintain the temple nicely and negotiate with a San

Francisco printer.

Since the

environs of the temple and its atmosphere remind us of Swamiji, we

cannot properly say that we are without him. His presence is felt even

more intensely, and for the first time we begin to understand what is

meant by worship in separation being the most ecstatic rasa.

Haridas,

Mukunda, Shyamasundar, Gurudas, Jayananda, Subal, Upendra. And the

weeping girls: Janaki, Malati, Yamuna, Harsharani, Lilavati.…

We all have

to console one another and see that the little storefront stays afloat

in the Haight-Ashbury. After all, Swamiji promised to return in three

months.

“Chaitanya

Mahaprabhu showed the way of the perfect devotee,” Swamiji’s words

remind us. “Worship in separation. When Krishna left Vrindaban, the gopis

were maddened in His absence. For the rest of their lives, they shed

tears for Krishna. They acted in many strange ways; this is told in the

Shastras. Rendering service in the rasa of

separation elevates us to the highest level of perfection, to the

platform of the gopis.”

End of Chapter 9

|