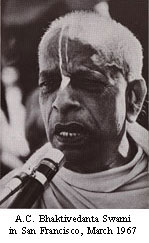

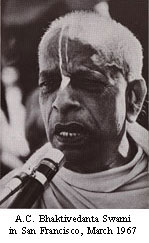

Part II: San Francisco, 1967

By Hayagriva das

Flowers

for Lord

Jagannatha

Printer

Friendly Page Printer

Friendly Page

The days of

February are beautiful with perfect temperatures in the seventies, fog

rolling off early, skies very blue and clear, sun falling bright and

sharp on the lush foliage of Golden Gate Park. The park encloses the

largest variety of plant and tree life to be found in any one spot on

earth. We are at a loss to identify plants for Swamiji.

“When

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu passed through the forests, all the plants, trees

and creepers were delighted to see Him and rejoiced in His presence.

Plant life is like that in the spiritual sky—fully conscious.”

“And these

trees, Swamiji? How conscious are they?”

“Oh, spirit

soul is there, but consciousness has been arrested temporarily.

Perception is more limited.”

Swamiji

strolls by men playing checkers, passes beneath the tall oaks, past the

shuffleboard court, then stops and turns to speak.

“Just see.

Old people in this country don’t know what to do. So they play like

children, wasting their last precious days, which should be meant for

developing Krishna consciousness. Since their children are grown and

gone away, this is the natural time for spiritual cultivation. But no.

They play games, or get some cat or dog and lavish their affection on

it. Instead of loving and serving God, they love and serve dog. But

love and serve they must.” He shakes his head, and again looks at the

shuffleboard court. The old men shout as they slide the disks toward

the numbered squares. “This is most tragic,” Swamiji says. “But they

don’t want to listen. Their ways are set. Therefore we are speaking to

the youth, who are searching.”

Walking

further into the park, we pass through the rhododendron dell, where the

bushes are heavy with clusters of white and pink flowers. We pass a

tennis court, then arrive at the park museum. Swamiji suggests

introducing a Krishna exhibit. Our artists, Jadurani and Haridas, can

be represented. They must paint more pictures.

“Such a

beautiful park,” he says. “Here in America you have all facilities. All

you lack is Krishna consciousness. If everything here is used in the

service of Krishna, that would make a first-class country.”

Returning to

the temple, we pass “Hippy Hill,” a favorite spot where young people

sunbathe, chat, sing, make love, and smoke marijuana. The cops have

given up on Hippy Hill. It’s the one place the hippies can go and be

granted peace.

“You

Americans are striving so hard for happiness,” Swamiji says. “But there

is no need to strive. Happiness and distress come and go. Just as

distress comes without our searching, happiness comes also. We don’t

have to search for either. But if we cultivate Krishna consciousness,

our distresses will be mitigated.”

We drive

across Golden Gate Bridge to Muir Woods, home of 3,000-year-old

redwoods. Walking down the path under the tall, blue-green canopy,

Swamiji reads the little signs before the largest trees, then looks up

reflectively at the boughs.

“These trees

are made to stand here for thousands of years because of their

attachment to sex,” he says. “We do not know what kind of body nature

is going to give us next. Perhaps she will put us in a body like this.

Then we will have to stand for so many years in one place.”

He then tells

the story of Nalakuvara and Manigriva, sons of Kuvera, the treasurer of

the demigods. These two brothers, although great demigods, fell prey to

wine and women, and one day, when drunk, entered the Ganges and sported

naked with young girls. While they were thus frolicking, the sage

Narada passed by, but Nalakuvara and Manigriva were too drunk to hide

their nakedness. Desiring their welfare, Narada turned them into trees,

immobilizing them so they could do no further harm. With their full

consciousness intact, the brothers stood long years as twin trees in

Nanda Maharaj’s courtyard, where the child Krishna often played. One

day, because baby Krishna had been a naughty butter thief, His mother

tied him to a large, wooden mortar. When this mortar lodged between the

two trees, baby Krishna, with His superhuman strength, pulled the trees

down. Out of these trees the two demigods, suddenly liberated, arose

with bodies shining like fire, and praised the Lord with prayers and

hymns.

“Being a tree

is a kind of curse for those overly sinful,” Swamiji says. “But for

Nalakuvara and Manigriva, it was ultimately Narada’s blessing.”

After an

hour’s stroll, we leave Muir woods, returning along a winding seacoast

road. The abrupt curves and dips cause Swamiji to get carsick. When he

complains of dizziness, we have to slow down.

“When I first

came to America on the Scindia boat, I was seasick,” he says. “But on

the plane from New York, I felt only a little popping in the ears. The

plane is better.”

Back at the

temple, Swamiji feels quite sick. Kirtanananda and Ranchor tend him in

his apartment, where he rests until the evening lecture.

“In this

material world, we are captured by sex life and put into prison,” he

tells us. “Just today I saw one prison in the bay surrounded by water.

What was that?”

“Alcatraz,”

someone says.

“Yes. So many

arrangements are made there to keep the prisoners entrapped. Now we are

in the prisonhouse of the body. And what is our entrapment? Sex life.

As long as we do not know that our happiness is with Krishna, we will

try to enjoy this material world, and so be bound by sex life.

Actually, we are suffering, but we think we are happy because of sex.

Here we are subject to miseries arising from the mind and body, from

other living entities, and from calamities of nature. These miseries

cannot possibly be avoided. Just like this afternoon, when I was coming

from Muir Woods, I felt uncomfortable due to some bodily pains. This is

going on, and it is always the same: sometimes bodily pains, sometimes

mental anxiety, sometimes national disturbance, or someone else giving

us trouble. Now you are thinking that if you just end the Vietnam war,

you will have peace. But there can never be peace here. This place is

meant for misery, and so misery will come in one form or another. That

is the nature of this material world.

“The great

sage Rishabadev said that this material atmosphere is nothing but sex

attachment. That’s all. You will find this attraction not only in human

society but in animal society, bird society, insect society, every

society. And if you go to the upper planets, to the abodes of the

demigods, you will also find sex attraction. Even Indra, the king of

the demigods, was very sexually inclined. And Lord Brahma, the highest

living entity, had a beautiful daughter to whom he was attracted. And

when Krishna, playing tricks, appeared as a very beautiful girl before

Lord Shiva, Shiva became mad with lust. So when Lord Brahma and Lord

Shiva become mad, what is our position? We are cats and dogs in

comparison.”

The hippies

sit quietly, eyes opened wide, surprised not to hear Swamiji advocating

sex, drugs, rock and roll, and passivism. They are used to so-called gurus

from India telling them, “Enjoy! Enjoy!”

“A guru

is not some pet, some fad,” Swamiji says. “He is not a conversation

piece. No. One must find the bona fide spiritual master and surrender

to him. That is the injunction of Bhagavad-gita. Guru

must be followed.”

“Are you an

authority on self-realization?” someone asks.

“Yes,”

Swamiji says. “Of course, I do not know whether I am an authority, but

my spiritual master has authorized me to do this. I ... I...” Swamiji

hesitates a moment, seeming almost embarrassed. “I don’t think myself

an authority. I am just trying to serve the order of my spiritual

master. That’s all. But being an authority is not very difficult.

Simply, if you try to understand Bhagavad-gita as Arjuna

understood it, you will become self-realized. It is not a very

difficult job. Unfortunately, people apply their own scholastic ideas

in different ways, and so murder the whole process.”

The more

radical hippies and Vietnam war resisters want more than peace in

Vietnam. They want a recognition of the “solidarity of man,” the

institution of a new world state conceived in planetary instead of

“tribal” terms.

Swamiji

accuses the hippies of placing man before other

planetary inhabitants, other citizens.

“You talk of

peace while eating meat,” he says. “You speak of peace while

slaughtering your mother cow. And you are surprised when there are

wars.…

“Solidarity

means more than talking of universal brotherhood while eating an

animal. There will never be universal brotherhood until we recognize a

universal Father and all living entities as His sons. That is the real

basis for solidarity.”

Once the mantra

rock dance honeymoon is over, Swamiji escalates his attacks against

sense gratification, insisting in every lecture that spiritual progress

is incompatible with drugs, laziness, and illicit sex.

“Krishna does

not tell Arjuna, ‘I will fight. You just sit on the chariot and smoke ganja.’

No. Although Krishna is God and can easily kill everyone on the

battlefield, still He wants His devotee to act on His behalf ‘Just be

My instrument,’ He tells Arjuna. ‘And fight with detachment.’ Fighting

is Arjuna’s duty as a kshatriya. By fulfilling his duty, he

does not incur sin.”

“What about

the draft?” someone asks.

“Our students

are being trained as brahmins,” Swamiji says. “They should not

be forced to act as kshatriyas, or warriors. Besides, a kshatriya

fights on religious principles. Now, people are just dogs fighting over

bones. That’s all.”

“But Bhagavad-gita

takes place on a battlefield, and Krishna tells Arjuna to fight.”

“Anything

done for Krishna becomes immediately spiritual,” Swamiji explains.

“Arjuna’s duty as a kshatriya is to fight. If he fights for

Krishna, following Krishna’s instructions, then his fighting is

spiritual. It is his salvation.”

“No! No!”

Although some

people walk out in protest, a few show more than a passing interest.

When the hippies become more serious, Swamiji discourages listening to

mundane music and encourages shaving off hair and beards and exchanging

bellbottom dungarees for robes.

“So when

people see you, they are reminded of Krishna. That is the meaning of sadhu—one

who reminds others of Krishna.”

Still,

Swamiji is not insisting on robes and shaved heads. These are mentioned

in passing. A few choose to shave and wear robes; most do not. No one

is pressured.

“Whatever

service you can render to Krishna—that is accepted.

There are

more initiations: Gurudas and Janaki’s sister Joan, who takes the name

Yamuna-dasi, Subal and his wife Krishna-dasi, Goursundar and his wife

Govinda-dasi, Haladar-dasi, Ramanuga, Uddhava, Upendra. They all help

Haridas and Harsharani manage the temple. Shyamsundar and Mukunda are

always planning some Big Event to surpass the mantra rock

dance. Rabindra-svarupa loafs around and dabbles in the Ouspensky cults.

I rent an

electric typewriter, set it up in the back temple room, and continue

typing up stencils for Back To Godhead, writing and

editing while Harsharani sends people after food, and cooks noon prasadam.

We take a

poll and discover that all thirty of our full-time members are

unemployed. When Swamiji suggests that we get jobs, there is some

shuffling. Some members hawk The Oracle and other

psychedelic newspapers to the tourists on Haight.

Somehow, we

feel, the Radha Krishna Temple will survive the whoop and holler, the

ephemeral glitter of psychedelia.

In early

February, Kirtanananda returns to New York with instructions from

Swamiji to go to Montreal and open the third ISKCON center.

“That boy

Janardan is there,” Swamiji tells him. “You can join with him and form

a temple. He speaks French and can translate nicely, and you can guide

the temple. It is not difficult. Just follow the program that we have

here, and when you have a place ready, I will come.”

When we see

Kirtanananda off at the airport, we wish him good luck opening the

first center outside the United States. “Maybe we’ll become an

international society after all,” I tell him. We speak of centers

multiplying all over the world, like chain letters.

Goursundar

and his wife Govinda-dasi, from Texas, are new devotees who have never

been hippies. Every morning at six-thirty, they knock on the temple

door to awake me. I tie on my dhoti and run to let them in.

Sometimes there are two or three visitors waiting with them, hippies

who have stayed up all night and are just coming down from LSD and

following Ginsberg’s advice to “stabilize their consciousness on

re-entry.”

One such

“stabilization” occurs at two in the morning, when I’m awakened by

pounding and screaming and police lights. As I open the door, a young

man with red hair and beard plunges in, crying, “O Krishna! Krishna! O

help me! O don’t let them get me! O for God’s sake, help!”

A cop sticks

his head in. “We brought him by here,” he smiles, “thinking maybe you

can help him.”

“I’m not

comfortable in this body!” the boy screams.

The police

leave, and the boy starts chanting furiously. He turns white and sweats

profusely. Sheer terror. I spend the rest of the early morning chanting

with him until Goursundar and Govinda-dasi knock.

Re-entry

stabilization becomes an ISKCON community service.

Sometimes,

when Swamiji arrives in the early morning, Goursundar, Govinda-dasi,

and I are the only ones in the temple.

“Where are

the others?” Swamiji asks.

It is

embarrassing to try to answer. Haridas, Shyamasundar, and Malati live

but a fifteen minute walk away. Mukunda and Janaki live just upstairs.

Gurudas and Yamuna are ten minutes away. Where are they?

“All this

sleeping is not good,” Swamiji says. “It is in the lowest mode, the

mode of ignorance. Life is meant for learning about Krishna

consciousness, but most of our time is wasted—the first eighteen years

in childishness, the last ten or fifteen in old age. So what does that

leave us? Some thirty good years at the most. And if half of that is

spent in sleep, what do we have?”

Gradually,

morning attendance picks up.

Being the

only person living in the temple proper, and one of the senior devotees

besides, I’m naturally looked to as the temple commander, a role I

often find myself regretting. Apart from re-entry cases, there are the

little black boys hanging around the back of the temple, waiting for a

hippy girl to go into a trance so they can snatch her purse. Chasing

the boys away is as futile as trying to keep flies from dung. Finally,

I have to caution the women to guard their purses.

“People come

here to have their consciousness raised,” Haridas protests. “You can’t

be telling them that.”

He’s right,

of course. I have to stand guard at the door. The Negroes blow smoke

rings in.

And the

Hell’s Angels occasionally enter like storm troopers, demanding ham

sandwiches and beer, threatening to kill me when I ask them to take off

their boots.

On the

brighter side, I’m in charge of organizing the daily sankirtan

party. After noon prasadam, we walk down Haight Street chanting

Hare Krishna, pounding drums, and ringing cymbals. By the time we reach

the Print Mint—only two blocks from the park—a dozen hippies are

following us, strumming guitars and shaking tambourines. Sometimes I

play an old trumpet, and sometimes a horn made from the kelp I’d found

on the beach. The kelp horn is my favorite, its be-dooo be-doooo

resounding for blocks.

No one on

Haight Street is over thirty. The hippies have hardly had time to

degenerate. Fresh from LSD visions, they follow us with springy gaits,

smiles, shining eyes—all somehow mythic, romantic, naive.

The record we

made in December, called “Krishna Consciousness,” is finally released,

and the Psychedelic Shop often plays it. We stop by their meditation

room and chant while the shop fills up. Then we circle back to Golden

Gate Park, past the little pond at the entrance, and onward to a big

field where boys play baseball and throw frisbees. We set up flags and

a rented kettledrum, and the people on Hippy Hill join with flutes and

bongos. After the kirtans, many return to the temple. And some

eventually become initiated devotees.

Apart from kirtans,

I find myself spending many sunny hours in the park, walking past the

tennis courts to large, quiet bowers surrounded with hybiscus and

eucalyptus. And at times I sit in the shade beneath the white and pink

rhododendrons and edit Bhagavad-gita. After editing, I

sometimes visit the museum and stroll through the replica eighteenth

century gardens, chanting my daily rounds while perusing the curlicues

of rococo art.

I generally

avoid the Japanese Gardens. They are glutted with out-of-state tourists

who look on us as drug-crazed hippies. Defending middle-class America,

the cops try to keep the hippies out of the area.

One morning,

Rabindra-svarup, Haladar, Subal and Krishna-dasi insist on going there.

I join, and am soon shocked to see Rabindra-svarup suddenly fall on his

knees and offer obeisances to a bronze statue of the Buddha.

The most

excited cop I’ve ever seen runs up, flailing his club. “What do you

think you’re doing?” he shouts. “Come on! All of you get outta here!”

A crowd

gathers.

“That crazy

man was trying to worship a statue,” a little boy says. “But the

policeman got him.”

Ravindra-svarup

seems to enjoy all the attention, as if it’s a chance to preach.

“You mean

it’s against the law to worship Lord Buddha?” he asks.

The cop

glowers and checks identifications. His face is fiery red. The people

about us are also smoldering.

“The mind is

on fire,” I recall the Buddha saying. “Ideas are on fire. Mind

consciousness is on fire. Impressions received by the mind are on fire

.…”

“Our

spiritual master says that Buddha is an incarnation,” Rabindra-svarup

continues, intent on being martyred, “and is to be paid all respects.”

The cop

swallows his anger and finally escorts us out.

“You

Americans are always setting Lord Buddha out on the lawn,” Swamiji

comments when I mention the incident. “But you shouldn’t put your

superiors where birds can drop stool on them.

February 27.

We drive down to Palo Alto for an engagement in the student lounge of

Stanford University. Swamiji sits on one of the lounge’s coffee tables

and starts leading the kirtan, chanting into a microphone. At

first, only twenty students are present, but as we chant and dance,

more congregate.

Then

something miraculous happens. The chanting and dancing sweep across the

room. Students who have never heard the

mantra before are jumping up and down, shouting the words with

abandon. Again, Swamiji weaves magic. He chants for an hour before

bringing the clamorous kirtan to an end.

Afterwards,

he explains the words of the mantra and the basic philosophy of

nonidentification with the material body.

“If you want

real happiness, you must abandon the illusion that ‘I am this body,”‘

he tells the students. “This Hare Krishna dance is the best process for

getting out of this illusion. You did not understand the words, but you

still felt the ecstasy of dancing. Language is not necessary. The sound

itself will excite the spirit. If you practise this, your life will be

perfect. It is not expensive, and you don’t have to undergo hardships

and exercises. You don’t have to put your head down between your knees.”

“Why should

we do this dance?” one student asks.

“Because it’s

good for you,” Swamiji says.

“Why is it

good for me?” the student persists.

“Keep

dancing, and you’ll find out.”

There are

some questions about the philosophy. Then someone asks whether or not

students should respond to the Vietnam draft. I brace myself.

“If your

country orders you, there’s no harm in going,” Swamiji says matter of

factly.

Faces drop.

Icy stillness. Both students and faculty look at one another.

“How is there

no harm in killing people?” a bearded professor asks warily.

“There is a

difference between killing in war and murder,” Swamiji says. “If a

soldier kills in war, following the order of a superior, he is

decorated. If he kills on his own account, he is hanged. So there is a

difference. On the Battlefield of Kurukshetra, Arjuna was following

Krishna’s orders to kill; therefore he did not incur sin.”

“No! No!” the

students begin to shout. Some walk out. Swamiji looks calmly at his

suddenly irate audience.

“On the

transcendental platform, nothing is wrong, nothing is right,” he says.

“When you do what your government orders, then how can you be

responsible? You’re simply following orders given by your superior.

Your superior is responsible. You’re responsible only in so far as you

elect that superior. When you had monarchy, you had to do what one

person told you. But now you have abolished monarchy and have

instituted democracy, a government of the people, and now you elect

your own officials. So now that you are making your own government, why

do you complain when that government tells you to go to war?”

The issue

becomes more heated. Students begin to raise their voices in anger.

“Nazi!”

someone shouts. “Fascist!”

Order

degenerates as everyone shouts his opinion at once. Swamiji picks up

his cymbals to start another kirtan, and we begin chanting. The

students and faculty look bewildered. No one takes up the chanting. A

few stay and argue, but most leave.

In the

morning, we read Swamiji the front page account in the Palo Alto

Times:

ANCIENT

TRANCE DANCE FEATURES SWAMI’S VISIT TO STANFORD

There’s a new dance about to sweep the country called the Swami.

It’s going to replace the frug, watusi, swim and even the good old barn

stomp. Why? Because you can do any old step to it and at the same time

find real happiness. You can rid yourself of the illusion that you and

your body are inseparable.

The write-up

goes on to describe the kirtan:

Before

the night was over, the audience of 250 was stomping, swinging and

chanting to the beat of Indian instruments and the words of the holy

Sanskrit Vedas, Hare Krishna, Hare Rama. They chanted

this without interruption for seventy minutes.

I’ve never seen

Swamiji more pleased with a news article. Fortunately, there is only

brief mention of the war issue.

“Very nice,”

he says. “You can make copies of this. What are they calling that

dance? The Swami?” He laughs. “Yes. Now we must make more engagements

at universities. This is our first, and now I’m thinking that there is

great potential.”

Later,

beneath the newspaper photograph of students dancing at the Palo Alto kirtan,

Swamiji types: “Everyone joins in complete ecstasy when Swami

Bhaktivedanta chants his hypnotic Hare Krishna.”

Then, in

early March, unannounced and unexpected, Lord Jagannatha, the Supreme

Lord of the universe, graces us with His presence, transforming San

Francisco into New Jagannatha Puri.

His arrival

is most extraordinary. A longhaired, barefoot young man enters one

morning with a curious wooden carving tied to a string around his neck.

Only two inches high, the artifact cost the boy seventy-five cents at a

local import warehouse.

From the

viewpoint of Indian art, the carving is an anomaly, more in an African

or American Indian primitivistic style. The long, semicircular head is

flat, and the arms are but tiny sticks jutting out from the sides. The

torso is a legless rectangle, and the eyes are big black disks. Two

dots serve for a nose, and the mouth is a curved line drawn upward in a

smile. We guess that the carving has something to do with Vaishnavism

by the white tilak markings on the face.

“There are a

lot of them in stock,” the boy tells me. “You can have this one, if you

like.”

Curious about

the tilak marking, I take the carving to Swamiji.

“What is

this, Swamiji?” I ask, setting it before him on his footlocker.

Swamiji’s

eyes widen in surprise, and he smiles. “Oh, that is Lord Jagannatha,”

he says. “That is Krishna.”

“Krishna?” I

look hard at the carving, trying to catch some remote resemblance to

other depictions of the Lord. I see none, but it somehow seems

appropriate for the Lord of the universe to look out on His creation

with such a blissful, superhuman smile.

“This is Lord

Krishna as He is worshipped in the great temple of Jagannatha Puri,

Orissa,” Swamiji explains. “There, He resides with His sister Subhadra

and brother Balarama.”

Swamiji then

relates the history: One King Indradyumna of Puri had commissioned

Visvakarma, the master sculptor who worked for the demigods, to carve

him statues of Lord Krishna, His brother Balarama, and sister Subhadra.

Visvakarma agreed on one condition: that he would be allowed to

complete his work in seclusion. No one was to look at the Deities

before They were completed; if They were seen before completion, he

would quit work altogether. When the King agreed, the sculptor began

his work behind closed doors. At the end of a month or so, the King

became impatient and asked Visvakarma when he would be finished. “A

little longer, Visvakarma told him. Months passed, and again the King

received the same reply. A year passed, and the same reply. Finally,

after waiting for such a long time, the King’s patience ended, and he

burst into the sculptor’s room. Visvakarma, who was an incarnation of

God, immediately vanished, leaving three incompleted statues in the

center of the room. Although unfinished, the statues were so esteemed

by the King that he had Them placed in the temple and worshipped

opulently.

“They were

carved in wood?” I ask.

“Yes. And

every year the Lord leaves the temple for the beach, and in Jagannatha

Puri there is a great procession. People come from all over India to

see the Lord travelling to the beach in His car.

“Car?”

“A kind of

car. Great carts. It is a yearly procession that thousands and

thousands come to see. When Lord Chaitanya first walked into the temple

and saw Lord Jagannatha, He said, ‘O, here is Krishna!’ and fell down

in a trance of ecstacy, and did not come out for days.”

“Can we have

Lord Jagannatha here?” I ask.

“Oh yes! We

must! We must welcome Him. After all, He has come of His own accord. We

did not have to search Him out. This is most auspicious. It is

Krishna’s will that we have Lord Jagannatha in San Francisco.”

Swamiji also

notes that this is most appropriate because of Lord Jagarmatha’s

special benefits: His compassion extends even to those addicted to bar

and brothel, and His worship does not entail all the elaborate

strictures of Radha-Krishna Deity worship, a worship, he says, that he

will one day teach us when we are more advanced. But for now, Lord

Jagannatha is the perfect Deity form for Kali-yuga America, and

especially hedonist California.

Of course,

the two-inch carving is too small to serve as anything but a model;

therefore Swamiji asks Shyamasundar, a very competent sculptor, to

carve a much larger Jagannatha. Hoping to find a better model,

Shyamasundar and I search through the stock of the import house and are

delighted to discover a more detailed sixteen-inch Jagannatha. We also

find two similar Deities. We rush them to Swamiji.

“This is

Subhadra, Krishna’s sister,” Swamiji explains, “and that is Balarama,

Krishna’s brother. So, Shyamasundar, you can carve all three and make a

special altar in the temple. Then I will install Them.”

Shyamasundar

buys three wooden blocks, each three feet high, and begins carving on

the roof of his Haight Street apartment. I stop by daily to watch the

progress. His work goes remarkably fast. In a very short time, by

mid-March, the Deities are ready and brought to the temple. Above

Swamiji’s dais, Shyamasundar constructs a plain redwood altar. At

night, we raid Golden Gate Park and return with boxes of flowers for

the installation.

The

Jagannatha Deities are beautiful indeed, and amazingly accurate

reproductions. Swamiji is pleased.

“Krishna has

given you the intelligence,” he tells Shyamasundar. “You have done it

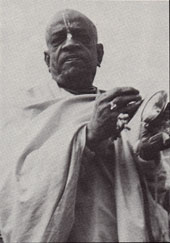

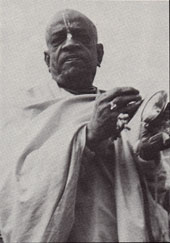

so nicely.” At the installation, Swamiji performs a new ceremony in

which he offers incense, fire, water, cloth, and flowers to Lord

Jagannatha, circulating these items while ringing a small bell.

“This is

called aratik,” Swamiji explains, passing the candle around.

Following his example, we briefly feel the flame’s heat with our hands,

and then touch our hands to our foreheads. “In this ceremony, we take

the heat of the flame. This is the advent of Jagannatha Swami, and now

the temple is ready for this worshipping process. Krishna is a person,

and we have to make friendship with Him. Just like we have to make

connections if we want to see someone very great, we have to introduce

ourselves in a friendly way, a loving manner, to Krishna. If we want to

transfer ourselves to that supreme planet, Krishna-loka, then we have

to prepare ourselves to love Krishna. Love of God. We must be

intimately in touch with God by love. We cannot claim any favor from

the Supreme unless we are in love with Him. There are six loving

reciprocations by which we can understand that we love someone. First,

you must give something to one you love. And then you must accept

something from him. Then you must give him something to eat, and accept

what he gives you to eat. Then you must disclose your mind to him, and

then listen to what he has to say. According to

Shastra, these are the six loving exchanges between Krishna and His

devotees.

“So I request

you devotees, when you come to the temple, to bring one fruit and one

flower to offer Lord Jagannatha. It need not be costly. Whatever you

can afford. Now, distribute prasadam.“

Harsharani,

Malati and Janaki hand out paper plates. It is a candlelight feast, and

Swamiji insists that we give

prasadam to spectators on the sidewalk.

“Very nice

preparations,” he says. “All glories to the cookers!”

Lord

Jagannatha Himself is an instant success. In the morning, devotees run

out to buy the two-inch version to make into a necklace. Soon Lord

Jagannatha is dangling about everyone’s neck. The problem, however, is

attaching the string. A small eye-screw in the top of the head is soon

nixed.

“You must not

put holes in the Lord’s head,” Swamiji tells us.

We finally

resort to glue.

Swamiji

teaches us a new mantra especially for Lord Jagannatha,

chanting it to a beautiful melody:

Jagannatha swamin nayana patha gami bhavatume. Translation:

“Lord of the universe, kindly be visible unto me.”

Late at night, when the temple is empty, I sit happily before Lord

Jagannatha chanting this mantra.

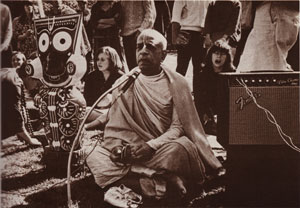

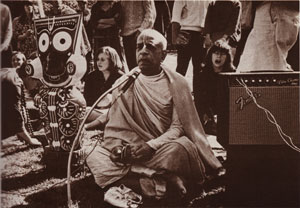

The next day,

thinking that everyone would like to see Lord Jagannatha, we carry Him

to Golden Gate Park for a kirtan. The hippies love Him. Within

minutes, just below the shadow of Hippy Hill, hundreds are dancing

about Him and chanting. Jagannatha’s large, round eyes stare out at the

bizarre American spectacle. His smile seems even more amused. Seeing

the large crowd He has attracted, I run back to get Swamiji. The next day,

thinking that everyone would like to see Lord Jagannatha, we carry Him

to Golden Gate Park for a kirtan. The hippies love Him. Within

minutes, just below the shadow of Hippy Hill, hundreds are dancing

about Him and chanting. Jagannatha’s large, round eyes stare out at the

bizarre American spectacle. His smile seems even more amused. Seeing

the large crowd He has attracted, I run back to get Swamiji.

“We’ve taken

Lord Jagannatha to the park,” I say, “and everyone’s chanting.”

“You’ve

what!?”

Swamiji hurries with me to the park. When he sees Lord

Jagannatha on the grass, surrounded by hippies dancing, he offers

obeisances, touching his forehead to the ground. Seeing this, we also

offer obeisances. Then Swamiji sits on the grass beside Lord Jagannatha

and starts chanting with us. More people come. Shyamasundar and Mukunda

rush back to the temple and return with an amplifier and speakers,

kettledrum, our array of colorful flags on poles, and a cushion for

Swamiji to sit on. Leading the chant, Swamiji strikes his cymbals

loudly and sings into a microphone: “Hare Krishna! Hare Krishna!

Krishna! Krishna!” Dancing around Swamiji and Lord Jagannatha, we chant

into the late afternoon. Swamiji hurries with me to the park. When he sees Lord

Jagannatha on the grass, surrounded by hippies dancing, he offers

obeisances, touching his forehead to the ground. Seeing this, we also

offer obeisances. Then Swamiji sits on the grass beside Lord Jagannatha

and starts chanting with us. More people come. Shyamasundar and Mukunda

rush back to the temple and return with an amplifier and speakers,

kettledrum, our array of colorful flags on poles, and a cushion for

Swamiji to sit on. Leading the chant, Swamiji strikes his cymbals

loudly and sings into a microphone: “Hare Krishna! Hare Krishna!

Krishna! Krishna!” Dancing around Swamiji and Lord Jagannatha, we chant

into the late afternoon.

Back at the

temple, Swamiji tells us that Lord Jagannatha is arca-vigraha,

the Lord manifest in the material world for our worship, and therefore

should not be treated like an ordinary statue made of wood. His

chastisement is mild but final. Back at the

temple, Swamiji tells us that Lord Jagannatha is arca-vigraha,

the Lord manifest in the material world for our worship, and therefore

should not be treated like an ordinary statue made of wood. His

chastisement is mild but final.

“The Deity

should never leave the temple,” he says. “The Deities don’t go out to

see the people except on special occasions. If you want to see the

Deities, then you have to visit Them.”

Lord

Jagannatha’s presence quickly beautifies the little Frederick Street

temple. Garlands are made for Him daily, and also for Subhadra and

Balarama. Vishnu paintings by Jadurani arrive from New York, and

Govinda-dasi paints a large portrait of Swamiji, which we hang beside

the dais. We also hang up Krishna prints distributed by India’s

Brijbasi Company and sold at Haight Street psychedelic shops.

I personally

consider the Brijbasi popular religious art somewhat garish, but

Swamiji tells us that the technique doesn’t matter. What is important

is that the pictures are of Krishna and consistent with scriptural

descriptions. Although they may be imperfectly drawn, they are

beautiful for the devotee because they remind him of Krishna.

One print, a

special favorite called Murli Manohar, depicts Krishna as a dark

cowherd boy, holding His flute to His lips, standing in his famous tribunga

posture, one leg crossed in front of the other. In the background, the

River Jamuna flows in the moonlight, and peacocks sport along the river

banks.

When Swamiji

sees this picture, he smiles and quotes a Sanskrit verse:

smeram

bhangi-traya-paricitam saci-vistirna-drstim

vamsi-nyastadhara-kisalayam ujjvalam candrakena

govinddakhyam hari-tanum itah kesi-tirthopakanthe

ma preksisthas tava yadi sakhe bandhu-sange ’sti rangah

“My

dear friend, if you still have an inclination to enjoy material life

with society, friendship and love, then please do not see the boy named

Govinda, who is standing in a three-curved way, smiling and skillfully

playing on His flute, His lips brightened by the full moonlight.”

Although a

theologian may call this a super-romantic conception, Krishna certainly

appeals to California youth. His boyish sports contrast sharply with

the asceticism of Buddha and sufferings of Christ. While Christ

suffers, and Buddha fasts and meditates, Krishna dances with a hundred

and eight cowherd girls in the Vrindaban forests. For many in the

Haight-Ashbury, Lord Krishna—with His adolescent good looks, long hair,

peacock feathers, garlands, bare feet, rings and beads, flute, girl

friends and companions—is none other than the Ultimate Hippy.�

End of Chapter 8

|

The next day,

thinking that everyone would like to see Lord Jagannatha, we carry Him

to Golden Gate Park for a kirtan. The hippies love Him. Within

minutes, just below the shadow of Hippy Hill, hundreds are dancing

about Him and chanting. Jagannatha’s large, round eyes stare out at the

bizarre American spectacle. His smile seems even more amused. Seeing

the large crowd He has attracted, I run back to get Swamiji.

The next day,

thinking that everyone would like to see Lord Jagannatha, we carry Him

to Golden Gate Park for a kirtan. The hippies love Him. Within

minutes, just below the shadow of Hippy Hill, hundreds are dancing

about Him and chanting. Jagannatha’s large, round eyes stare out at the

bizarre American spectacle. His smile seems even more amused. Seeing

the large crowd He has attracted, I run back to get Swamiji. Swamiji hurries with me to the park. When he sees Lord

Jagannatha on the grass, surrounded by hippies dancing, he offers

obeisances, touching his forehead to the ground. Seeing this, we also

offer obeisances. Then Swamiji sits on the grass beside Lord Jagannatha

and starts chanting with us. More people come. Shyamasundar and Mukunda

rush back to the temple and return with an amplifier and speakers,

kettledrum, our array of colorful flags on poles, and a cushion for

Swamiji to sit on. Leading the chant, Swamiji strikes his cymbals

loudly and sings into a microphone: “Hare Krishna! Hare Krishna!

Krishna! Krishna!” Dancing around Swamiji and Lord Jagannatha, we chant

into the late afternoon.

Swamiji hurries with me to the park. When he sees Lord

Jagannatha on the grass, surrounded by hippies dancing, he offers

obeisances, touching his forehead to the ground. Seeing this, we also

offer obeisances. Then Swamiji sits on the grass beside Lord Jagannatha

and starts chanting with us. More people come. Shyamasundar and Mukunda

rush back to the temple and return with an amplifier and speakers,

kettledrum, our array of colorful flags on poles, and a cushion for

Swamiji to sit on. Leading the chant, Swamiji strikes his cymbals

loudly and sings into a microphone: “Hare Krishna! Hare Krishna!

Krishna! Krishna!” Dancing around Swamiji and Lord Jagannatha, we chant

into the late afternoon. Back at the

temple, Swamiji tells us that Lord Jagannatha is arca-vigraha,

the Lord manifest in the material world for our worship, and therefore

should not be treated like an ordinary statue made of wood. His

chastisement is mild but final.

Back at the

temple, Swamiji tells us that Lord Jagannatha is arca-vigraha,

the Lord manifest in the material world for our worship, and therefore

should not be treated like an ordinary statue made of wood. His

chastisement is mild but final.