Part II: San Francisco, 1967

By Hayagriva das

Swami

in Hippyland

Printer

Friendly Page Printer

Friendly Page

January 17,

1967. When Swamiji descends from the plane and enters the San Francisco

airport, he is greeted by a group of about fifty young people. As he is

questioned by the press, he extends his usual transcendental

invitations.

“We welcome

everyone, in any condition of life, to come to our temple and hear the

message of Krishna consciousness,” he says.

“Does that

include Haight-Ashbury hippies and bohemians?” a reporter asks.

“Everyone,

including you or anyone else,” Swamiji says. “Whatever you are—what you

call an acid-head, or hippy, or whatever—what you are doesn’t matter.

Once you are accepted for training, you will change.”

“What is your

stand on drugs and sexual freedom?” another reporter asks.

“There are

four basic prerequisites for those entering this movement,” Swamiji

says. I do not allow my students to keep girl friends. I prohibit all

kinds of intoxicants, including coffee, tea, and cigarets. And I

prohibit meat eating and gambling.”

“And LSD?”

“I consider

that an intoxicant. I do not allow my students to use that or any other

intoxicant.”

This

announcement provokes the reporters to question Allen Ginsberg, who is

first at the airport to touch Swamiji’s feet in obeisance. As poet

laureate of the beatniks and now acknowledged patriarch of the hippies,

Allen presided over the recent “Gathering of the Tribes,” when a

hundred thousand in Golden Gate Park celebrated the arrival of “the

psychedelic age.”

“Well, you

might say that the Swami is very conservative,” Allen answers. “That

is, conservative Hindu. You might even say he is to his faith what the

hard-shell Baptist is to Christianity.”

“Conservative?

How is that?” Swamiji asks, concerned.

“In respect

to sex and drugs,” Mukunda suggests.

“Of course,

we are conservative in that sense,” he says. “That means we are

following Shastra [scriptures]. We cannot depart from Bhagavad-gita.

But conservative we are not. Personally Lord Chaitanya was so strict

that He would not even look on a woman, but we are accepting everyone

into this movement, regardless of sex, race, faith, caste, position, or

whatever. Everyone is invited to come chant Hare Krishna. No, we are

not conservative.”

As Swamiji

walks down to the baggage claims, the new devotees strew flowers before

him and garland him. While waiting for the luggage, he raises his hands

and begins to dance. Ranchor holds an umbrella over him against the

sunlight. Allen also begins to dance and chant, and differences are

forgotten. While dancing, Swamiji gives a flower to each person who has

come to welcome him.

“SWAMI

INVITES THE HIPPIES!” the San Francisco Examiner

headlines. “SWAMI IN HIPPYLAND,” the Chronicle reports,

describing Swamiji’s welcomers as belonging to the “long-haired,

bearded and sandaled set.” San Francisco newspapers are busy creating

the hippy image. “Hippy,” a word recently popularized by the papers, is

big news, guaranteeing good street sales.

The Frederick

Street storefront that Mukunda rented is only two blocks from Golden

Gate Park, the world’s most beautiful arboretum. It is a small

storefront, very much like Matchless Gifts, but brighter, thanks to a

large plate glass window. Above the front door, a sign announces: RADHA

KRISHNA TEMPLE. Incense and candles burn on a small altar at the end of

the room. Next to the altar is Swamiji’s dais of purple cushions, the vyasasana,

the seat for the representative of Veda Vyas, elevated a little above

the devotees who sit on buff carpeting.

Posted on the

walls and in the front window are reprints from The East Village

Other write-up, and a reprint of the photo of Swamiji standing

in Tompkins Square Park. The caption: BRING KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS WEST.

From the

beginning, the kirtans are more lively than in New York. The

dancing is free and vigorous, the temple packed with young people with

long hair, beards, exotic clothing, beads, Indian trinkets, paper

stars, and skin paint. Chinese papier-mache lightshades cover the bulbs

hanging from the ceiling. God’s-eye Huichol crosses also dangle from

strings. Beside the dais hangs a painting of Lord Chaitanya and His

disciples, copied by Haridas last year.

Haridas

(Harvey Cohen) is president of the San Francisco temple. In his early

thirties, Haridas is a little older than most of us. He has a

short-cropped beard and sincere, inquiring blue eyes. He’s an artist

from New York. Articulate, he suavely manages to keep everyone at

peace—hippies, Hell’s Angels, straights, and devotees. I tell him that

I appreciate his painting of Lord Chaitanya and His disciples.

“Oh, when I

first saw the original, I thought they were all women,” he says. “And

when Swamiji saw my copy, he looked at the breasts and said, ‘No. This

will never do.’ I figured he liked them Rubenesque. So I made them even

larger.”

“Crazy

artists,” Swamiji laughs when I mention this.

Haridas had

met Swamiji as early as fall, 1965, when Swamiji was visiting Dr.

Mishra’s upstate Ananda Ashram.

“I used to go

up there on weekends,” Haridas tells me. “You know what it’s like.

Everyone’s into his own thing. Well, one night when I was in my room

reading, Swamiji walked in and told me that there were higher forms of yoga

than Mishra’s hatha-yoga. Now up to this time, I’d been

fascinated by this little old man sitting in the corner chanting beads.

He never joined the discussions but just sat there, a great presence in

the corner, chanting a rosary. Really captured my attention. So you can

imagine the impact when he entered my room and said, “Bhakti-yoga

is the highest. It is the science of God devotion.’ When he said this,

I realized that he was speaking the truth, and it was as if I’d never

heard it before. I felt that he was reading my soul. All my questions

were answered without my even asking. And I thought, ‘Here’s my

teacher.’ As if all my life had just been preparing for this moment.”

“I know the

feeling,” I say. “Others describe it very much in the same way.”

“It was

really strange,” Haridas muses. “His words were so simple, yet they

seemed to come from the deepest wisdom. I actually lost all sense of

place and time. It was life’s focal point. After that, for the rest of

the weekend I kept looking at him. He sat so calmly and had such

dignity and warmth. He asked me to visit him when we returned to the

city, and of course I did. His room was a tiny office in the back of

Mishra’s Yoga Society in the West Seventies, and I began to visit

regularly.”

“And Mishra?”

“He was

always travelling a lot. Swamiji was asked to speak a few times, but it

was so obvious that this was a real spiritual master that it became

embarrassing. So he rarely lectured. I would just go to his room, and

we’d sit there on the floor, facing each other and chanting. He had

only a typewriter, a new tape recorder, a box of books he’d brought

from India, and a color reproduction of Lord Chaitanya and disciples.

He looked at this picture often, and when he found out that I was an

artist, he asked me to paint it.”

Reminiscing,

Haridas seems wistfully longing to return to those days. I realize that

for him, nothing will ever quite equal those intimate moments in New

York, when Swamiji was alone and unknown. Now he is surrounded by

disciples and guarded jealously by young Ranchor, who is tactless and

sometimes even insulting.

“You mean

we’re going to have to contend with him every time we want to see

Swamiji?” Haridas complains.

I mention

this to Swamiji.

“Do you

expect everyone to be to your liking?” he asks, smiling.

Swamiji’s

apartment on Frederick Street, next to the temple, is a little smaller

than his New York apartment, but the furnishings are the same:

typewriter, dictaphone, books, sleeping pad, and a footlocker full of

manuscripts.

“Translating

goes on,” he says.

Mukunda has

also managed to rent an apartment down the hall, as quarters for

himself and Janaki. Here, I meet two new San Francisco devotees

Shyamasundar and his wife Malati. They talk excitedly about the “mantra

rock dance” scheduled for the Avalon Ballroom.

“Some big

bands have promised to come,” Shyamasundar tells me. “Grateful Dead,

Moby Grape, Janis Joplin and Big Brother.

The names

mean nothing to me. I know only the Rolling Stones and The Beatles.

“There’s a

whole new school of San Francisco music opening up,” Shyamasundar

explains. “Grateful Dead have already cut their first record. Their

playing for us is a great boost, just when we need it.”

“But Swamiji

thinks that even Ravi Shankar is maya, “ I point out.

“Oh, it’s all

been arranged,” Shyamasundar assures me. “All the bands will be on

stage, and Allen Ginsberg will introduce Swamiji to San Francisco.

Swamiji will talk and chant Hare Krishna with the bands. Then he

leaves. There should be about two thousand people there.”

At night, I

sleep on the floor in the room behind the temple. Through the wall I

can hear a jukebox blasting rock and roll late into the night. The

Diggers—a sort of hippy Volunteers of America—are our neighbors.

The

Haight-Ashbury atmosphere is festive, carnivalesque. Hippydom is riding

the media crest. Thousands flock daily to San Francisco wearing flowers

and bellbottoms and shaking tambourines. “Be-in’s” abound, celebrations

of nothing more than “being there.” People are assumed to be high on

LSD, or at least pot. Corporate, middle-class America cries out to put

an end to it all. Close down the Haight before it happens!

President

Johnson sends more troops to Vietnam. More draftcards are burned in

protest. More longhairs flock to the Coast, many crowding the temple

for morning prasadam, looking for a place to eat and crash.

At seven in

the morning, however, there are only six devotees present.

“Where’s

everybody?” I whisper to Mukunda.

“Oh, they’ll

be in later,” he says sleepily.

Swamiji looks

around. The night before, the temple had been packed.

“They are

sleeping?” he asks. “That is not good. Too much sleep.”

He chants the

invocation (Samsara-dava) and Hare Krishna, then begins to

lecture on Bhagavad-gita.

“Mantra

is a combination of two words,” he says. “Man means ‘mind,’ and tra

means ‘delivered.’ So, the Vedic mantras or hymns are meant for

delivering us from mental concoctions. Our present difficulties are

experienced on the mental and psychological planes. The psychedelic

movement is on this platform. They are speaking of expanding the mind,

but you should know that beyond the mind is the intelligence, and

beyond the intelligence is the soul. So the mantra delivers us

from this mental-psychological plane and establishes us on the

spiritual.”

A half dozen

people drift in from the street. They are disheveled and dirty,

obviously up all night in the park. They reek of pot.

Swamiji

speaks of the Absolute Truth. He stresses the need for tapasya,

penance.

One boy with

long, straight blond hair begins mumbling and twitching. His milk-white

skin turns almost as red as his headband bandanna.

Swamiji

likens human sex life to that of the animals. He points out the

necessity for purification.

The boy

finally explodes, shouting, “I’m God!” Then screaming, “Iiiiiyam God!”

I look at

Mukunda, wondering what to do. Mukunda ignores the boy and keeps his

eyes on Swamiji.

“What’s

that?” Swamiji asks.

I look at

Haridas. He’s shaking his head, indicating that the boy is to be

ignored.

“What’s

that?” Swamiji asks again.

“He’s saying

that he is God,” Mukunda says.

Swamiji holds

his head back, looking down at the boy through his reading glasses.

Having observed enough, he returns to the text of Bhagavad-gita

and his commentary.

“Without

accepting and undergoing some penance, we cannot purify our existence,”

he says, “and without purifying our existence, we cannot enjoy our

nature as Brahman.”

“Iiii’m God!”

“So if we

follow the scriptural regulations, our conditioned existence will be

purified, and we shall begin our spiritual life of unending happiness.”

“God!”

“Are there

any questions?”

“I’m God!”

Everyone

looks around, but no hands are raised. The boy sits before me in the

center of the temple, his face now more pink than red. There’s a long

silence as Swamiji looks about, then picks up his cymbals.

“So chant

Hare Krishna,” he says.

Clapping, we

start the morning melody. Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna,

Hare Hare, Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.

The blond boy

jumps up. “I’M GOD!” he screams furiously. “I’M GOD!” He beats his

chest, and the hard thumps resound like a mridanga. “I am! I

am!” The chanting almost drowns him out. Mukunda, smiling, starts

dancing, and the boy screams repeatedly, “I’m God, I’m God, I’m God!”

The rhythms blend.

He turns and

dashes out of the temple, still striking his chest. He runs down

Frederick Street, flailing his arms and screaming until he’s out of

sight and hearing.

After kirtan,

Swamiji returns to his quarters with Mukunda and Janaki. Guests are

scheduled for nine.

I ask Haridas

why he didn’t throw out the boy when he interrupted the lecture.

Brahmananda would have removed him at the first outburst.

“You have to

be careful with the hippies here,” Haridas tells me. “Tactful’s the

word. If someone’s high on LSD, people automatically give him all the

respect of God. They come in and jump up and down and scream, but we

can’t lay a hand on them because they’re LSD saints. Had we kicked that

boy out, the whole neighborhood would be down on us. The Diggers next

door are pretty noisy, but they unplug their jukebox during lectures,

and they’ve been giving us clothing and helping decorate the temple.

Sometimes the Hell’s Angels go over there and raise a lot of noise, and

sometimes they even come in here. If they do, best to humor them. They

are always trouble.”

As if cued,

someone at the Digger’s begins to roar like an animal. Thuds, breaking

glass and screams follow. Some girls run inside, close the door and

lock it.

“Oh, don’t go

out there!” one girl cries. “It’s the Angels! They’ll tear you to

pieces!”

Harsharani is

serving breakfast prasadam. She sets out extra paper plates.

“There’ll be more guests,” she says quietly.

The shouts

and thuds continue, ceasing only when the police and ambulance arrive.

A big black has just beaten up three Hell’s Angels.

The door is

opened, and a dozen people drift in, all talking about the fight.

Harsharani brings out more prasadam.

Harsharani,

Janaki, and Jadurani are the first girls initiated in the movement. In

New York, people are still asking whether the temple “accepts girls,”

but in San Francisco the girls take to Krishna from the very beginning.

After all, Krishna is eternally young and beautiful. He has nothing to

do but sport and play His flute. He loves to dance. He’s the

heart-breaker in everyone’s heart. Girls naturally flock to Him.

The San

Francisco temple certainly abounds in pretty girls. Swamiji begins

performing weddings weekly.

“Why have you

chosen the center of Hippyland for your temple, Swamiji?” a Chronicle

reporter asks.

“Because the

rent’s cheap,” Swamiji replies.

Brahmananda

phones frequently from New York. He tells us that at first they were

wondering whether they could manage without Swamiji, but now they are

surprised by how easy it is to carry on.

“The

chanting’s the focal point,” Brahmananda tells us. “We can always sit

down and chant.”

He adds that

Swamiji’s presence is being felt in a different and even more wonderful

way.

“We’re

beginning to understand how worship in separation is more relishable.”

Swamiji likes

San Francisco. In the early mornings, he walks past Kezar Stadium, down

Stanyan to the entrance of Golden Gate Park. We follow, chanting

softly, down the narrow trails to the rhododendron dell. Some devotees

pick a few flowers for the temple, and from time to time Swamiji stops

to ask about a flower or a certain tree.

“A tree has

to endure so much,” he says, “due to very sinful previous lives. Trees

are forced to stand many years and suffer.”

After the

walks, Swamiji receives visitors from an array of societies, including

the Haight-Ashbury Cultural Institute, whose members want to make Hare

Krishna a prominant part of the new “Hashbury” culture that’s about to

“change America.” Swamiji even attends their roundtable meeting,

chanting his beads quietly, eyes closed, enduring the cigarette smoke

and lengthy chit-chat. When he’s finally called upon to speak, he says,

“Make Krishna your center. With Krishna as your center, you’re bound to

succeed. But if not, then what can you accomplish?”

Zen Buddhists

come. And strange new LSD Christian sects. The Brotherhood of the

Golden Swan. All the members dress like Franciscan friars and chant,

“Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.” They call themselves yogis.

Swamiji is most gracious; he allows them to speak briefly in the

temple. The Buddhists, however, he does not invite to speak.

Swamiji

continues translating Bhagavad-gita. He is so eager to

print it that we begin negotiations with a local printer. Prices are

very high. In New York, Brahmananda continues his pursuit of publishers.

“And Mr.

Payne?” Swamiji asks. “And the money? And the building? Either we get

the building or he should give us our five thousand back. And that Mr.

Kallman—where is the record he promised?”

Mukunda

explains the importance of the upcoming dance. We discuss the program

with Allen Ginsberg. Allen is to introduce Swamiji and then lead the

chant.

“The melody

you use is difficult for group chanting,” I tell him.

“Maybe,”

Allen admits, “but that’s the melody I first heard in India. A

wonderful lady saint was chanting it. I’m quite accustomed to it, and

it’s the only one I can sing convincingly.”

Although

joyful enough, his melody is too erratic for large groups.

We consult

Swamiji.

“Don’t you

think there’s a possibility of chanting a tune more appealing to

Western ears?” Allen asks.

“Any tune

will do,” Swamiji says. “That’s not important. What’s important is that

you chant Hare Krishna. It can be in the tune of your own country. That

doesn’t matter.”

Daily now,

more youths crowd outside the temple looking for lodging. The

Haight-Ashbury vibrations lure them out of their suburban homes and

send them hitchhiking west, often penniless, with backpacks and

sleeping-bags and dreams of adventure. What strange amalgamations!

Chinese, Japanese, Mexicans, Anglos, Indians, blacks. And now Hare

Krishna. On the wall of the Ashbury Cinema, someone has scrawled, “DOWN

WITH THE CASTE SYSTEM!”

What bizarre

fantasies! People can become whatever they want in Haight-Ashbury. On

the streets, they present a kind of historical pageant, looking at

times like characters from the Old West, or princes and peasants from

medieval Europe. It is strange to see them enter the temple, strange to

hear Swamiji preaching to them, dutifully reminding them that they’re

not young forever, that the body doesn’t abide, that Krishna is

awaiting us in the spiritual sky.

After

breakfast prasadam—oranges, farina with dates and brown sugar,

and hot milk—Haridas and I check out the stores down Haight Street,

concentrated in the half blocks leading to the entrance of Golden Gate

Park, their gaudy commercialism in stark contrast to the tranquility of

eucalyptus and oak.

We visit The

Print Mint, The Psychedelic Shop, The Omen. Every Wednesday evening, we

chant in the meditation room of The Psychedelic Shop. Hare Krishna amid

black lights, strobes, incense, Oriental tapestries, and dayglow

Tibetan mandalas.

Haight Street

is a tawdry carnival of psychedelia. It is drugs deified. Yet at its

root, there’s a basic disenchantment with materialism, the frustration

of Sisyphus, tired of rolling his rock up a hill over and over, longing

instead to cast aside his burden, break the chain of conditioning, and

surmount karma.

“Only Krishna

can liberate us from karma,” Swamiji tells us. “Therefore He is

also called Mukunda, He who grants mukti, liberation. No one

else has this power.”

So on the

racks beside the psychedelic publications, we place Back To

Godhead. “Where there is Godhead, there is light.” Although they

urge the hippies to abandon drug taking, they sell out faster than we

can mimeograph them.

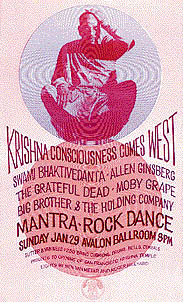

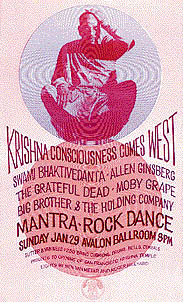

Sunday,

January 29. The night of Krishna consciousness at the Avalon Ballroom.

Haridas, Mukunda, Shyamasundar, Janaki and Malati go early to see that

everything’s set up. The ballroom is large, surrounded by mirrors. It

boasts the latest in strobes and slides. Two movie projectors whir full

time, and the sound system shakes the floor and walls. The Avalon and

the Fillmore are the two homes of the new San Francisco rock: Jefferson

Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Moby Grape, Quicksilver

Messenger Service, Grateful Dead, Steve Miller, Janis Joplin. All

young, white, and LSD oriented. Sunday,

January 29. The night of Krishna consciousness at the Avalon Ballroom.

Haridas, Mukunda, Shyamasundar, Janaki and Malati go early to see that

everything’s set up. The ballroom is large, surrounded by mirrors. It

boasts the latest in strobes and slides. Two movie projectors whir full

time, and the sound system shakes the floor and walls. The Avalon and

the Fillmore are the two homes of the new San Francisco rock: Jefferson

Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Moby Grape, Quicksilver

Messenger Service, Grateful Dead, Steve Miller, Janis Joplin. All

young, white, and LSD oriented.

“I think what

you are calling ‘hippies’ are our best potential,” Swamiji says.

“Although they are young, they are already dissatisfied with material

life. Frustrated. And not knowing what to do, they turn to drugs. So

let them come, and we will show them spiritual activities. Once they

engage in Krishna consciousness, all these anarthas, unwanted

things, will fall away.”

When the

Avalon’s doors open at seven, hippies, teenyboppers, and Hell’s Angels

begin pouring in. By eight o’clock, when The Grateful Dead begins

playing, the ballroom is packed. A barrage of rhythm, shrieks, and

blasts, amplified by speakers bigger than most closets, shake the

ballroom. There’s a roar of approval, and strobes flash off and on,

illuminating a sea of gyrating, pulsating bodies.

Swamiji

leaves Frederick Street at 9:30. He is dressed in fresh saffron silks.

As he discusses translating

Chaitanya-charitamrita, the sweet aroma from his gardenia

garland fills the car. By ten, he walks up the stairs of the Avalon,

Kirtanananda and Ranchor flanking him as he enters through the main

ballroom doors. Cigarette smoke mingles with incense. Janis Joplin

bellows into the microphone. Steel guitars, voices, drums, and strobe

lights bombard the senses. Yet Swamiji floats through it all, making

his way along the walls of the ballroom to the stage like a swan

navigating through lotuses.

Suddenly

Janis ends her song, and the slide show changes. Pictures of Krishna

and the demigods are flashed onto the wall. Krishna and Arjuna in the

chariot. Krishna eating butter. Krishna subduing the whirlwind demon.

Krishna playing the flute.

There’s a

spontaneous roar of approval, and as Swamiji sits beside Ginsberg on

the front center stage, the roar turns into an ovation. The bands also

come on stage. Swamiji is garlanded again and again.

Allen begins

his introduction, commanding attention with the expertise of a Pied

Piper. Swamiji sits quietly, his head held high, appearing like a

golden Buddha—regal, transcendental, saintly—a strange contrast to poet

Ginsberg.

Allen tells

how his own interest in Hare Krishna started in India five years ago.

Then he recounts how Swamiji opened his storefront on Second Avenue and

chanted Hare Krishna in Tompkins Square Park. “Now, Krishna

consciousness has come West, to the Haight-Ashbury,” he says, inviting

everyone to the Frederick Street temple. “I especially recommend the

early morning kirtans,” he adds, “for those who want to

stabilize their consciousness on LSD re-entry.“

Although this

is hardly devotional Vaishnavism, the audience maintains a reverential

silence. After Allen’s introduction, Swamiji speaks, giving a brief

description of the history of the mantra, beginning with Lord

Chaitanya. “It is particularly recommended for this age,” he says.

“Kali-yuga is an age in which men are short-lived, ignorant,

quarrelsome and always in difficulties. Yet regardless of our position,

we can always chant the maha-mantra.”

The Hell’s

Angels stare with mute incomprehension. Wearing denim jackets, caps,

leather regalia, chains, tattoos, long, dirty hair, they seem prime

candidates for the ghostly hordes of Shiva.

Swamiji

doesn’t mention the rules and regulations.

“Anyone can

chant the maha-mantra,” he says. “There are only three

words-Hare, Krishna and Rama. ‘Hare’ is the energy of the Lord. …

I doubt that

very much of his speech is understood, but everyone stands politely and

listens respectfully. As Swamiji explains the mantra, slides

flash the words on the walls. Then the chanting begins with Allen

slowly singing his hurdy-gurdy tune into the microphone: Hare Krishna,

Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare. The Big Brother band joins

in, then Grateful Dead and Moby Grape. Gradually, the chant spreads

throughout the audience. People begin holding hands and dancing.

Standing in front of the bands, we can hardly hear the audience, but

above everything is Allen’s voice, shouting, his “Hare” sounding more

like “Hooray!” Swamiji stands up and starts dancing, and the chanting

builds steadily to a climax. On the wall behind, a slide projects a

towering picture of Lord Krishna, flute in His hands, peacock feather

in His hair. A maze of color whirls to the rhythm of the mantra,

a rhythm that accelerates to a frenetic presto, the words merging,

punctuated only by Allen’s whooping “Hooray! Hooray!” Through the

flashing strobes, I see people dancing and shaking tambourines.

Then suddenly

the chanting ends, and all that can be heard is the loud buzz of

microphones.

Swamiji

offers obeisances to the gurus. “Ki jai! Ki jai! All glories to

the assembled devotees! Ki jai!”

It is all

over. As people meander to the soda stand, Allen announces that the

rock groups will shortly resume the concert. Swamiji descends from the

bandstand and walks straight through the heavy smoke and crowds to the

front stairs. Again, Kirtanananda and Ranchor follow.

“This is no

place for a brahmachari,” Swamiji proclaims, leaving.

The dance

nets us fifteen hundred dollars, barely enough to resolve the temple

debts.

In the

morning, the temple is crowded with celebrants from the Avalon. They

never went to bed.

Swamiji

lectures on the eternity of the spirit soul.

“It cannot be

drowned by water, burned by fire, nor dried up by the wind,” he says.

“And these everlasting souls are to be found everywhere—on the earth,

in the air and water, even in the sun. Souls can acquire bodies

adaptable to the atmosphere of all planets, but none of these bodies in

the material worlds can continue to be fresh. That is the material

limitation. The element of time is so strong that it breaks down

everything. Whatever you create, though it be very beautiful and fresh

now, will eventually fade away just like a flower. In time, flowers

grow very beautiful, but in due course they wither and vanish.

Similarly, you are all now young and with such beautiful bodies. And so

you say, ‘Let us enjoy.’ But your bodies will also wither and perish.

Nature’s course is like that. Therefore Krishna tells Arjuna not to

deviate from his duty by fleeing the battle.”

Later in the

morning, Kirtanananda and I drive Swamiji to the beach, where he chants

a mantra we’ve never heard before.

“Govinda jai

jai, Gopala jai jai, Radharamana Hari, Govinda jai jai.” He chants

slowly, yearningly, in a low baritone mingling with the peaceful

falling of the waves.

“Govinda is

Krishna, who gives pleasure to the cows and senses. Gopala is Krishna

the cowherd boy, and Radharamana is Krishna as the enjoyer of

Radharani. These are the words of this mantra.”

He chants a

longing, haunting melody that seems to reach out and then fall short,

and so must reach out again, like the perpetual mounting, crashing, and

mounting of waves striving to envelop the shore.

As he chants,

he walks slowly along the boardwalk. The January breeze is fresh and

cool. I peruse some kelp washed up on the beach and decide that the

long, hollow whips with their bell-shaped heads would make good

trumpets for kirtan.

Kirtanananda

gets a blanket and puts it over Swamiji’s shoulders. Swamiji looks out

over the Pacific expanse.

“Because it

is great, it is tranquil,” he says.

‘The image of

eternity,” I say.

“Nothing is

eternal but Krishna,” he says. Silence. Then: “In Bengali, there is one

nice verse. I remember. ‘O, what is that voice across the sea, calling,

calling, Come here... come here .… ?’”

For a long

time, Swamiji sits on a boardwalk bench, looking out across the ocean

and singing Bengali songs to Gopinatha, Lord Krishna, Master of the gopis.

From time to time, he stops to translate a verse for us. “O Gopinatha,

please sit within the core of my heart and subdue this mind, and thus

take me to You. Only then will the terrible dangers of this world

disappear.”

Then he sings

another verse, looking out on the ocean as if it were his audience. It

is a rare, peaceful moment, beyond everything material, and I wish it

could go on forever. But after a while, Swamiji stands up, sighs

deeply, as if beckoned by duty, and says, “Back to the temple.”

End of Chapter 7

|

Sunday,

January 29. The night of Krishna consciousness at the Avalon Ballroom.

Haridas, Mukunda, Shyamasundar, Janaki and Malati go early to see that

everything’s set up. The ballroom is large, surrounded by mirrors. It

boasts the latest in strobes and slides. Two movie projectors whir full

time, and the sound system shakes the floor and walls. The Avalon and

the Fillmore are the two homes of the new San Francisco rock: Jefferson

Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Moby Grape, Quicksilver

Messenger Service, Grateful Dead, Steve Miller, Janis Joplin. All

young, white, and LSD oriented.

Sunday,

January 29. The night of Krishna consciousness at the Avalon Ballroom.

Haridas, Mukunda, Shyamasundar, Janaki and Malati go early to see that

everything’s set up. The ballroom is large, surrounded by mirrors. It

boasts the latest in strobes and slides. Two movie projectors whir full

time, and the sound system shakes the floor and walls. The Avalon and

the Fillmore are the two homes of the new San Francisco rock: Jefferson

Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Moby Grape, Quicksilver

Messenger Service, Grateful Dead, Steve Miller, Janis Joplin. All

young, white, and LSD oriented.