Part II: San Francisco, 1967

By Hayagriva das

Soul Struck

Printer

Friendly Page Printer

Friendly Page

During April and May, tourism and

hippy fantasy soar to rare heights in the Haight-Ashbury. Like a Mardi

Gras carnival, the celebration is cresting, rushing toward some

indefinite Ash Wednesday.

Kirtans

are wild and uninhibited. We often chant at the Fillmore and

Avalon ballrooms, during intermissions between rock groups. A “Summer

of Love” festival is organized, and we chant at be-in’s in Golden Gate

Park, at the YMCA and Psychedelic Shop, and with hippy sun worshipers

at Morning Star Ranch.

The spring

passes so quickly, perhaps because its days are filled with

long hours of sunshine and festivity. Youths from all sections of the

nation roam and lounge throughout the park, barefoot and dungareed,

leisurely creating what they hope is a new community of love and peace,

a world where no one is over thirty, where there is no violence,

ignorance or death. And they chant Hare Krishna because they see ISKCON

as an exotic flower in the hippy bouquet, something even further

removed from twentieth century America, from the political activists

and their endless strife. Generally, activists and Negroes shun us,

considering us on far-out trips, dabbling in the cultures of

undeveloped nations.

But what do

they know of Krishna? Or of Swamiji? What do any of us

really know?

April 23,

Swamiji writes me:

I am

so pleased to learn that you are all feeling my separation. And so

I am feeling the same here. These feelings have very great

significance—namely that we are being gradually posted in real Krishna

consciousness. I am receiving many other letters from the devotees in

San Francisco and telephonic calls indicating their feelings of

separation, the basis of Lord Chaitanya’s mode of Krishna

consciousness. The more we feel like that, the better for our

advancement. However, from the physical point of view, as there is now

difficulty in going to Montreal, I may return to San Francisco

sometimes in the next month.

Swamiji

points out that any good typist can learn the art of Varitype

very quickly. If I will type Bhagavad-gita and Back

To Godhead, he will

get the machine. Satsvarupa, Rayarama and I would solve the “printing

problem.” He is prepared to invest $4,500 in a Varitype.

Simultaneously,

he is looking into opening branches in Baltimore and

Boston.

“Brahmananda,

Rayarama and Mahapurusha, three boys, have already gone

to Boston last night,” he writes, “to see the situation, and we shall

act accordingly.”

Again and

again we run into dead ends searching for a publisher or

reasonable printer. Then, as I feared, Swamiji writes me May 10: “I beg

to inform you that it has now been arranged to print Bhagavad-gita

in

India, and therefore you are requested to send me back all the

corrected manuscripts on receipt of this letter.”

We consider

this disgraceful, to our eternal shame that our spiritual

master has to send to India to have his book published. But there’s no

getting around the fact that commercial presses in the States want too

much money for our budget. Brahmananda pleads with Swamiji to give us a

little more time. Surely we will find some publisher who is interested.

In late May,

Kirtanananda leaves Montreal to visit Swamiji in New York.

“I hear he’s a little sick,” he tells me on the phone. He and Janardan

plan to stay only a few days, but once there, Kirtanananda decides to

remain. He phones me again on May 30.

“Swamiji’s

not feeling well,” he tells me. “He looks tired. He’s lost a

good deal of weight and looks quite exhausted.”

Not knowing

what to make of this, I tell no one.

June 1:

Kirtanananda phones again. I answer on the receiver behind the

temple. He is most distressed. Swamiji is in the hospital. He has had

some kind of stroke.

Bit by bit,

as Kirtanananda talks in a strained voice, the pieces fit

together. We should have seen it coming. Swamiji had been having heart

palpitations since our recording session in New York before Christmas.

He was also drinking more water, indicating high blood sugar, diabetes.

“The other

day, he was having palpitations,” Kirtanananda says. “He

didn’t look at all well, so I kept everyone out. He was disturbed by a

twitching in his arm. It was terrible.”

As I listen,

frightful images of Swamiji in pain arise. Dear Krishna,

help us! I recall Swamiji saying, “If anything happens to me, don’t

call a doctor. Just give me my beads. I just want to chant Hare Krishna

and go to Krishna that way.”

Kirtanananda

continues: “Well, we phoned a doctor, who gave him a shot

of penicillin and diagnosed a nervous condition complicated by the flu.

The doctor said that maybe he’s praying too much.”

“Praying too

much?!”

“Then

yesterday, when I was sitting in Swamiji’s room…” Kirtanananda’s

voice breaks. “While kirtan was going on downstairs, … the

twitching

began again, and Swamiji’s face began to tighten up, and his eyes

started rolling. Then all of a sudden he threw himself back, and I

caught him. He was gasping Hare Krishna. And then everything stopped. I

swear, I thought it was the last.… But then the breathing started up

again, and with it the chanting. He didn’t regain control of his body,

though. We called an ambulance. Now he’s in Beth Israel Hospital.”

Weeping,

almost inaudible over the long distance, Kirtanananda promises

to keep us posted. I hang up the phone and stand dumbly for a moment,

wondering what to do. In the temple, a few people are chanting.

Lilavati is making garlands for Lord Jagannatha. Harsharani is scooping

flour out of a barrel to make the evening’s chapatis.

“Where’s

Haridas?” I ask.

No one knows.

I run out to Stanyan. The sun is bright. Some hippies are

tossing frisbees across Frederick Street. I dash from apartment to

apartment until I find Haridas and take him aside.

“Kirtanananda

called,” I tell him. “Swamiji has had a stroke and is in

the hospital. He’s asked us to spend the night chanting.”

Haridas looks

as if he’s just been struck in the face. Worse—soul

struck. He stands, looking at me with silent disbelief, then shakes his

head sadly. “I knew it,” he says. “I could sense something horrible was

going to happen. Just look at that picture.”

He points to

a photograph taped to the wall, the photo of Swamiji’s

last look at the temple, his farewell look of infinite sadness. As we

look at the photo, we cannot weep. Weeping in itself is a finite,

inadequate release for an interior emptiness, the sense of terrible,

premature loss. We feel that a whole spiritual atmosphere is leaving us.

“We’ll never

see him again,” I say. “I know it. I just feel it.”

“Have you

told the others?” Haridas asks.

“No. I

couldn’t. They’re chanting in the temple. So happy.”

“Well, don’t

tell them yet,” he says. “We’ll try to find out more. Then

we’ll tell them tonight before the kirtan.”

Stunned,

Haridas and I wander to the park. I don’t want to see any of

the devotees. My face must tell all.

We sit at the

park entrance on a bench and chant quietly, alone with

our awful secret and countless unspeakable fears. Foremost, we fear

that with Swamiji’s passing, the Hare Krishna movement will

disintegrate. We have just begun; the very foundation has yet to be

completed. Swamiji’s teachings may be lost. There are no books

published apart from the few he brought from India, and even Bhagavad-gita

is unfinished.

I fear

personally for myself. What will I do without his words, the kirtans,

the little storefront temples, the quiet

moments in his room,

the casual conversations, the constant presence of Vrindaban and Lord

Krishna? I fear return to chaos and lonely searching.

How strange!

I recall that Swamiji’s horoscope predicted this attack.

Years earlier, an Indian astrologer had discerned some break there in

his seventy-first year, some inevitable climax. In fact, that is to be

his normal hour of death, the time fixed for him to leave the body.

En route

aboard the freighter Jaladhuta, a palmist told Swamiji that if

he survives his seventy-first year, he will live many more years.

The death

crisis is in his palm and in the stars.

“I will

always be with you,” I recall him saying. “The spiritual master

is always with the disciple. I am always feeling the presence of my

spiritual master.”

But we are so

young, so green, on such foreign ground for Vedic

culture. Maya will surely absorb us like a sponge. We are now

in no

position to lose our spiritual father.

Looking up

from the park bench, I see children playing in the sprinkler

and sunlit grass and wonder at the audacity of life to go on so

blithely.

I try to

phone Kirtanananda in New York, but he’s at the hospital. I

talk instead to Rayarama.

“All I can

really say is that Swamiji is very, very ill,” he tells me.

“He’s asking all of us to chant all night for his recovery.”

Haridas and I

assemble everyone in the temple and try to think of the

least shocking way to put it. Haridas looks at me and nods.

“I got a call

this afternoon from Kirtanananda,” I say finally.

“Swamiji has fallen sick.”

Janaki and

Lilavati immediately burst into tears. This quickly spreads

to the other girls. Sighing, I sit quietly, recalling that Socrates

banished women from his deathbed in order to die in peace.

Some of the

boys begin asking details. There’s very little to say

except that we’ve been requested to chant all night and pray to Lord

Nrishingadev for Swamiji’s health.

Lord

Nrishingadev is a fierce incarnation of Krishna—half-lion,

half-man—who descends to save His devotee Prahlad from Prahlad’s

demoniac father Hiranyakashipu. After Nrishingadev kills Prahlad’s

father, Prahlad recites the following prayer to pacify Him. It is a

prayer we immediately begin chanting.

tava

kara-kamala-vare nakham

adbhuta-shringam

dalita-hiranyakashipu-tanu-bhringam

kesava

dhrita-nara-hari-rupa

jaya jagadisa hare.

“O my Lord, Your hands are very beautiful, like the lotus flower, but

with Your long nails You have ripped apart the wasp Hiranyakashipu.

Unto You, Lord of the universe, I offer my humble obeisances.

We turn on

the dim altar lights behind the Jagannatha Deities, light

candles, and chant in the flickering shadows. It is solemn chanting and

even more solemn dancing. The news quickly spreads down Haight Street,

and soon the temple is crowded with visitors come to join our vigil and

chant through the night.

Mukunda and

Janaki phone New York. No additional information.

Kirtanananda is spending the night in the hospital beside Swamiji’s

bed. No one else is being allowed in. Hospital regulations. Yes,

there’s a vigil also in New York. Everyone’s chanting through the night.

We chant past

midnight. Most of the visitors leave, but none of us yet

feel sleepy. The chanting overtakes us in waves. My mind wanders to

Swamiji, to New York, to the future, to the past. I have to force my

errant mind back into the temple to confront the present, to petition

Sri Krishna to spare our master a little longer. And through the

chanting we all feel Swamiji’s presence, insistent, purely spiritual.

By two in the

morning, we begin to feel sleepy. I change instruments

just to keep awake, sometimes playing mridanga, sometimes cymbals or

harmonium. Many dance to stay awake. The girls serve light prasadam—sliced

apples and raisins. It is dangerous

to sit next to the

wall, an invitation to doze off. We are so frail. Only Arjuna, the pure

devotee, is Gudakesa, conqueror of sleep.

Between three

and four, the most ecstatic hour, the brahma-muhurta hour

before the dawn, we sense that if Swamiji is still alive, he will

surely pull through.

We sing. We

chant on beads. We chant through the usual seven o’clock kirtan

and into the late morning. Chanting fourteen

hours nonstop, we

cleanse the dust from the mind’s mirror. We sense Krishna and Swamiji

everywhere. Surely now he is well!

Just before

noon, Kirtanananda phones to tell us that Swamiji is still

living but is very, very weak. We should continue chanting. The doctors

are running all kinds of tests.

“It’s

terrible,” he says. “They’re shooting him with needles and taking

blood. They want to stick needles through the skull to check out the

brain waves. He doesn’t want all this, but he’s submitting because of

us. He’s simply putting himself in our hands.”

“What does he

want to do?” I ask.

“It’s hard to

tell. He’s still so weak. But he hasn’t indicated that

he’ll be leaving his body.”

I seize on

this as good news and tell Haridas and Mukunda. There is

some guarded optimism. But within we know that his body is old and has

suffered a stroke. He can go at any moment. We still await the call

that tells us.

June 3.

Swamiji has been in the hospital two days.

“He seems to

be responding to massage, Kirtanananda tells me. “He’s

talking some, talking about going to India to consult an Ayurvedic

physician. He just dictated a letter to a Godbrother in India

requesting Ayurvedic advice.”

“That sounds

good,” I say.

“He wants out

of the hospital,” Kirtanananda adds. “He’s still saying

that we never know when death will come, but he’s not concerned. He’s

saying that Krishna allowed him to survive his major attack because He

wants him to carry out his spiritual master’s orders to spread the sankirtan

movement in America.”

This news

elates us all. The next day, Kirtanananda tells me that

Swamiji is definitely gaining strength.

“His facial

expression is picking up,” he says, “and his chanting is

strong again. He’s not sleeping as much. Chanting all the time. This

morning, he was even able to put on tilak.”

But in the

evening, Rayarama phones to say that Swamiji passed a bad

day. Now it is touch and go. At times, he seems right on the brink of

death. At times, he’s about to leave the hospital. Reports continue to

conflict.

June 6.

“Swamiji wants to move to the country or seashore,”

Kirtanananda tells me. “He definitely wants out of the hospital. He’s

concerned about the money—a hundred a day here. And he says that

they’re not helping him, just sticking him with needles.”

Rayarama

informs us that they’ve rented Swamiji a little bungalow in

Long Branch, near the water. “Swamiji wants to be near the sea,” he

says. “He just wants a place to rest in peace. The hospital isn’t

helping him much.”

We speculate:

if he’s considering leaving the hospital, surely the

worst must be over. But how extensive is the damage? Will he ever be

able to lecture again, to write, to dance at kirtans in the

park, to

lead us on spiritual marathons until we drop? To be without him now is

what we have tacitly feared from the beginning. He has been

singlehandedly sweeping us along, rapidly transforming our lives with

daily revelations.

Yet so much

is but intimated! Bhagavad-gita As It Is still sits

incomplete, and much remains untold: the twelve cantos of Srimad-Bhagavatam,

Chaitanya-charitamrita, Vedanta-sutra,

Bhakti-rasamrita-sindhu. He had planned to

translate and annotate them

all.

“I have so

much to tell you,” he’s often said. “We haven’t even

scratched the surface. In our tradition, there are such wonderful

literatures! We must work quickly and publish.”

Will his

dream for a Vedic America dissolve like Don Quixote’s dream of

Spanish chivalry? It is sad to think of those spiritual epics remaining

hopelessly buried in the past, in old dusty tomes, stored on

bookshelves labeled “occult.”

But hasn’t he

sent Krishna vibrating through the air? Rolling off our

tongues? Hasn’t he brought Krishna Himself, the Person, to Second

Avenue? Tompkins Square? Golden Gate Park?

And now,

after giving us a glimpse of Krishna, will he leave us?

Despite

protesting doctors, Swamiji checks out of the hospital June 8.

Brahmananda and Kirtanananda immediately drive him to Matchless Gifts,

where he pays obeisances to his spiritual master and Krishna and then

leaves for the ocean bungalow in Long Branch.

Now

Kirtanananda writes that Swamiji “seems to be indestructible.” When

he hears our recording of “Narada Muni,” he sits up in bed and starts

to clap his hands.

“Is that an

American tune?” he asks.

Swamiji wants

to see a temple opened in Vancouver.

“There’s one

gentleman there.…”

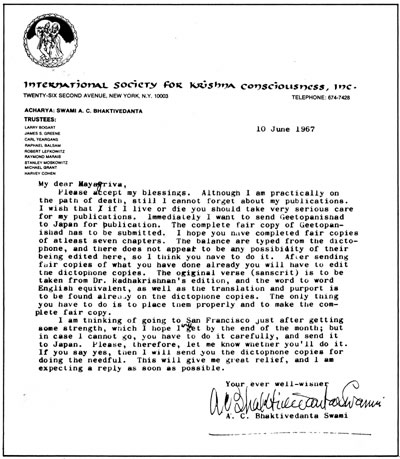

June 10, I

receive a letter from Swamiji himself: June 10, I

receive a letter from Swamiji himself:

Although

I am practically on the path of death, still I cannot forget

about my publications. I wish that if I live or die, you will take very

serious care of my publications. Immediately I want to send Bhagavad-gita

to Japan for publication. The

complete fair copy has to

be submitted. I hope you have completed fair copies of at least seven

chapters. The balance is typed from the dictaphone, and there does not

appear to be any possibility of editing here, so I think you have to do

it.…I am thinking of going to San Francisco just after getting some

strength, which I hope I will get by the end of the month; but in case

I cannot go, you have to do it carefully and send it to Japan. Please

let me know whether you’ll do it. If you say yes, then I will send you

the dictaphone copies for doing the needful. This will give me great

relief, and I am expecting a reply as soon as possible.…

The books! He

is on the brink of death, and his only concern is

printing Bhagavad-gita As It Is. His only reason for

being in the

material world is to spread Krishna consciousness, and books are the

“big mridanga,” self-contained kirtans that defy both

time and space,

that endure and travel far.

“Something

very wonderful happened today,” Kirtanananda tells me on the

phone. “We arrived at the bungalow around noon, and of course Swamiji

hadn’t had his lunch. I was trying to prepare it as fast as possible,

but by two o’clock it still wasn’t ready. Then he came into the

kitchen. ‘Where’s my lunch? Bring me whatever there is immediately.’ He

was furious. I made some excuse, which I shouldn’t have done, and

finished up whatever I had—dal, some chapatis and

vegetables. Then he

sat down in the kitchen and ate voraciously. It was really wonderful to

see.”

Such news

elates the temple. But the next day, we are discouraged by

conflicting reports. “Swamiji had a bad night and is feeling very bad.

We just don’t know what’s wrong.”

Only one

diagnosis is certain: He has diabetes. The doctors have given

him pills to try to control this, but he doesn’t want to take them. He

wants to cure himself by diet.

“He’s

managing this fairly well,” Kirtanananda tells me, “but he still

varies a great deal from day to day. Some days he’s well; other days he

feels bad. When he’s up, he’s making plans to return to San Francisco,

to go here and there. Then on bad days he just says, ‘Let me go back to

India.’ So we don’t know what we’re doing from one day to the next.”

Depending on

the latest reports from New York, the spirit of the San

Francisco temple vacillates. The Rathayatra Car Festival is coming up

July 9, just a few weeks away. We plan a parade down Haight Street to

the park and ocean, but what specifically are we to do?

“Swamiji says

that you should stay there and help organize the

Rathayatra,” Kirtanananda tells me. “He says that if you will organize

it nicely, he will come.”

“I don’t even

know what Rathayatra is,” I protest.

“Just

organize a procession,” Kirtanananda says, “from the temple to

the beach. You can get all the hippies to pull the Deities in large

carts. And afterward, distribute prasadam.”

More

confusion. Large carts? Haridas and I search through the public

library and manage to find a book with photos of the Rathayatra cart

used in Orissa, India. It is a large cart all right, made entirely of

wood, with enormous wooden wheels dwarfing the man standing beside

them. According to the book, people throw themselves under the wheels

to be crushed and instantly liberated. The cart itself, as big as a

galleon, is large enough to hold a hundred people. It has balustrades

and a flower garlanded throne for the Deities. It would take hundreds

of people to pull it, and the cops would no doubt consider it far too

dangerous to let loose on San Francisco streets.

Besides, we

could never construct such a thing in three weeks.

With great

joy I receive a long letter from Swamiji dated June 25.

I am

scheduled to come to San Francisco on July 5, but everything

remains on the supreme will of the Absolute Person; man proposes, God

disposes. As for my health, generally it is improving, but sometimes I

feel too weak. I hope that by another week, however, I will get

sufficient strength to fly to San Francisco.…

We send

Swamiji a Rathayatra announcement to encourage his coming. The

New York devotees report that he is looking well and is even playing kartals,

chanting, and lecturing a little.

Perhaps the

worst is really over!

“Swamiji says

that he’s definitely coming to the Rathayatra,”

Kirtanananda

announces. Everyone clusters about the phone.

“He’s

coming!” Shyamasundar shouts.

“Swamiji’s

coming to Rathayatra!” Mukunda tells everyone.

The next day,

another phone call, and a somber Kirtanananda.

“Now he says

he’s going back to India,” he tells me. “He’s not feeling

well. He wants to see an Ayurvedic doctor.”

This

ping-ponging continues through June while we wonder what to do

about Rathayatra. On weekends, Jayananda and I drive along the coast

looking for a cottage where Swamiji can rest in the ocean air.

At the end of

June, Swamiji leaves the Long Branch bungalow and returns

to the New York temple. After a scheduled hospital checkup,

Kirtanananda phones us. For the first time, he sounds really happy.

“The doctors

were amazed,” he says. “They can’t understand it. He’s had

a major stroke, and now, only three weeks later, he’s checking out

fine. When I asked if he could fly to San Francisco, the doctor said,

‘No reason not to.’ So we’ve made reservations for July 5.”

We act fast.

Mukunda rents a beautiful beach house at Stinson Beach, a

little resort just north of San Francisco. The estate, called

Paradisio, is complete with palms, flora, enclosed patio, sliding

windows and a lawn Buddha covered with bird droppings.

Mukunda had

to plead with the owners to get them down to two hundred a

week.

In New York,

Swamiji remains in his apartment. Although still not

attending kirtans, he is steadily recovering. We hear that he

has

initiated a new pastime—morning walks. At seven in the morning, he

walks with devotees down Second Avenue to Fifth Street and then to

First Avenue, where he sits on a bench to chant beads or just relax in

the early morning air. He then walks back to Matchless Gifts. These

walks become as much a ritual as any other.

Wednesday,

July 5, Kennedy Airport. Swamiji and Kirtanananda board

Delta Airlines flight 621. Something is wrong with one of the wheels,

and the plane is delayed about an hour.

We wait in

San Francisco with baskets of flowers.

End of Chapter 10

|